By Larry Peña

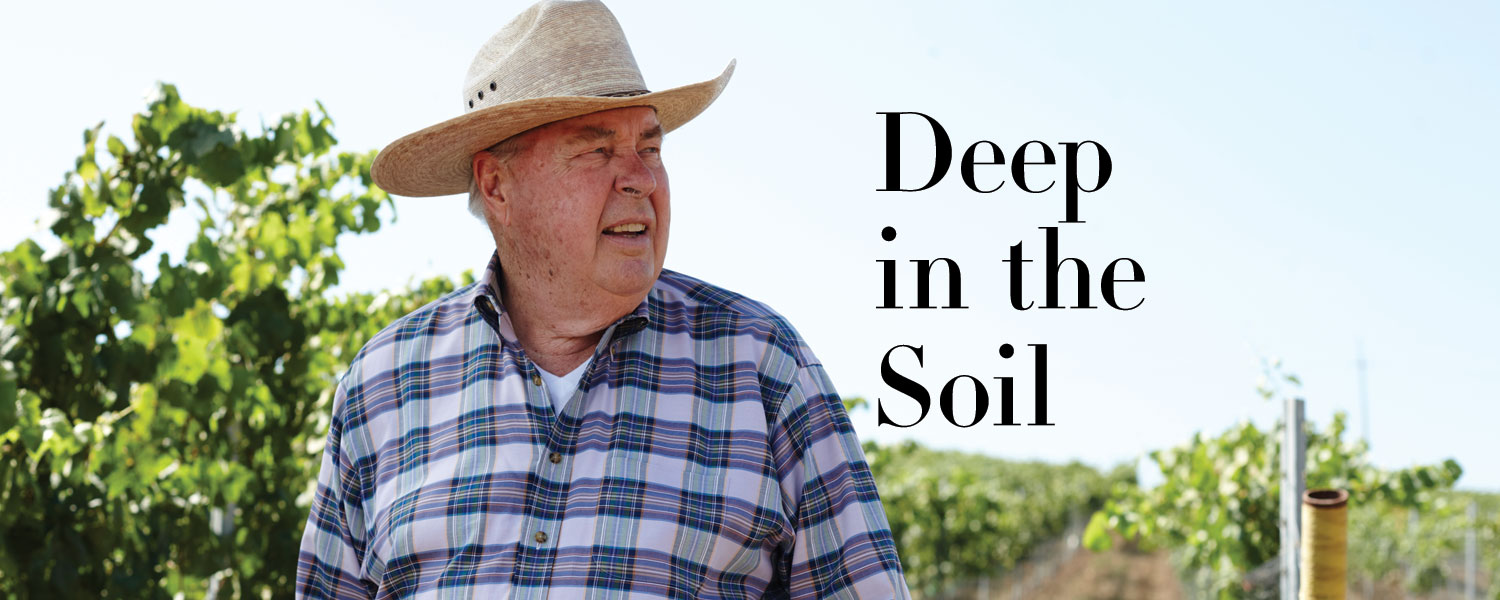

For Professor Victor Valle, food transcends the basic needs of human nourishment. This past year as a Fulbright Scholar in Mexico, Valle explored the deeper meanings of a unique cultural ingredient – the chile pepper.

Can a flavor express a culture? Can a scent make a memory? Can an ingredient give us a gateway into history? These are the questions Fulbright Scholar Victor Valle is seeking to answer in his forthcoming book, “The Poetics of Fire: Metaphors of Chile-Eating in the Borderlands.” His quest has taken him from the ancient Zapotec homelands of Oaxaca, to archives in Mexico City, and across the deserts of the U.S.-Mexico borderlands to chile roasting parties in New Mexico and farmers markets in California.

“In Latin America there has always been a lot of talk about the chile in a philosophical way,” says Valle, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and emeritus professor of ethnic studies at Cal Poly. “In ancient Mesoamerica, the phrase ‘the chile, the salt’ expressed the idea of sustenance, but from a perspective that did not distinguish the need for nutrition from the need for pleasure.

“I’m trying to keep it simple,” he says. “How do you see the world from the chile’s point of view?”

For Valle, the answer to that question begins in his childhood. Growing up in a Mexican-American family in Southern California in the early ‘60s, the flavors and smells of the chile were the quintessence of his formative years. In an opening passage of his book, he writes:

It snuck up from behind me — a sulfurous whiff of smoldering weeds, and then the tickle that comes just before coughing. A breeze wafted the charred aroma to the middle of the street, all the way from the kitchen window my mom had opened to vent the smoke of burgundy-colored chile de arbol pods twisting like witches’ claws on her cast iron griddle. Standing arms-length from her improvised comal for baking tortillas and toasting spices, she held a dishcloth over mouth and nose to protect them from fumes strong enough to drive pets away.

Although the topic is very personal for Valle, the scope of his work on this book goes far beyond his own past. “Part of this project is exploring how the chile has played in history,” he says. “I’m looking at the colonial period of Latin America and how Europeans talked about the chile in their chronicles — then looking at how natives, creoles and mestizos responded to that language.”

During the 1500s and 1600s, Spanish colonization included a deliberate attempt to eradicate or suppress indigenous Mexican religions and ways of thinking. But Valle’s research pursues the myriad ways in which an indigenous culinary culture persisted, against all odds. “The DNA of that original culture is still there, and the chile is a powerful representation of that,” he says. “That’s why it is so important.”

On his trip, Valle followed the historical route of the chile from Southern Mexico up to the border. That path was a deliberate choice. In the colonial period, the Spanish inadvertently helped spread the very cultures they were trying to eradicate. They sent their allies, the Tlaxcalans, northward to establish agricultural infrastructure required to continue mining operations in the borderland territories of today’s state of Chihuahua. The Tlaxcalans took their chile seeds and farming techniques with them, actually helping to spread Mesoamerican cultivars, cooking and farming practices up throughout the borderlands.

Along the journey, Valle turned to archival sources. Working with a portable scanner, he sought out historical and literary chile references in obscure texts, many of them available only in Mexican archives and libraries.

The original scope of his work called for a focus on the colonial period — the heady impact point of vastly different cultures in conflict. However, he soon discovered older, pre-Hispanic myths that gave a prominent importance to the chile’s sensual connotations. Some of the earliest stories he uncovered date to the time of the Toltecs, who predated the Aztec civilization, dominating central Mexico around 1000 A.D.

Other parts of the project were more visceral. In Southern Mexico, Valle explored the roots of indigenous Mexican cooking with Abigail Mendoza Ruiz, a renowned chef who is working to keep the native Zapotec culture and cuisine alive. Everywhere he went, he tasted examples of local dishes that featured distinctive chile varieties.

“I’ve met people who have taken me to eat at a lot of local places, who have prepared dishes made with rare chiles like Huacle and an endangered species called Tabiche,” he says. “I’ve eaten a lot of really good food.”

Valle’s previous book, “Recipe of Memory: Five Generations of Mexican Cuisine,” co-authored with his wife Mary Lau Valle, was a more personal and less ambitiously academic work. Part family memoir and part cookbook, “Recipe of Memory” earned nominations in 1996 for two Julia Child Cookbook Awards and a James Beard Award.

Although that book attained only modest sales, Valle says that the critical acclaim it received inspired him to pursue one of the ideas it contained: an aesthetic philosophy underlying Mexican cuisine’s flavor principles. Over the intervening years, his studies in urban theory, literature and ecology have inspired him to return to those questions through the lens of one incredibly complex ingredient and its evolving meanings. That’s what he hopes to accomplish in “The Poetics of Fire.”

“We’re at a moment in history when the idea of writing about food and philosophy is coming back,” he says. “But we need a different language of food to understand it as art.”