Team Madden

The football legend’s family takes us behind the scenes of his remarkable life and unexpected journey into stardom.

When John Madden’s future wife asked Cal Poly physical education Director Robert Mott if he could get her fiancée a job on campus, Mott looked her in the eye quizzically.

“Are you seriously thinking about marrying this fellow?” he asked. “It’s the biggest mistake you’ll ever make in your life.”

Madden’s 1958 Cal Poly yearbook photo.

More than six decades later, Virginia Madden, widow of one of the most legendary coaches and commentators in football history, smiled at the memory.

“Sixty-two years,” she said. “I think it turned out okay.”

The Pro Football Hall of Fame coach, Emmy-winning broadcaster and Cal Poly alumnus passed away in December 2021, following a 38-year career in professional football and just after celebrating his 62nd wedding anniversary with Virginia, a fellow Mustang. But it wasn’t always success after success: Throughout his career, John had to figure out how to make the most of both unexpected setbacks and opportunities with the support of his most important teammates: his family.

At 6’4″ and 260 pounds, John was a massive presence at Cal Poly when he transferred there in 1957 on a football scholarship. Among his teammates and around campus, he was known as “Whale.” As a football player, John played both offense and defense and was also a catcher for Mustang Baseball while studying physical education.

Madden (right) with Mustang football teammate Pat Lovell.

During his final year at Cal Poly, John was drafted into the NFL by the Philadelphia Eagles. His lifelong football dreams were about to come true — but were quickly dashed when a knee injury in training camp ended his professional career before it began.

With no other prospects in Philly, he returned to San Luis Obispo, where he met Virginia — not on campus, but on a night out at Harry’s Nightclub and Beach Bar in nearby Pismo Beach. Virginia, who was at the bar with two friends, recalls John coming in with a few football teammates and taking up an entire table.

“I have no idea how he got up the courage to ask me to dance,” she said. “John couldn’t dance.”

They had a lengthy dance floor conversation, where “John told all sorts of lies,” about his life and career, and Virginia mentioned she was taking night classes at Cal Poly. They left the bar separately, but for the next three weeks, Virginia noticed that John just happened to be hanging around wherever she was on campus.

“Finally, after about the third week of this, he was hanging around outside the coffee shop, and I walked out and said, ‘Do you wanna talk to me?’ And he said, ‘Yes, I’d like to take you home.’ Well, I lived about 56 miles from campus, so I told him he probably didn’t. But I let him drive me to my carpool pickup spot.”

As their relationship blossomed, John landed tickets to the Pro Bowl in Los Angeles and invited Virginia. But tragedy struck: Virginia’s dad passed, and she immediately went home to Los Alamos, California to be with her mother. Instead of going to the game, John hitchhiked to Virginia’s family home to comfort her in her grief.

“He showed a lot of compassion and seemed to understand what I was going through, and that my first obligation was to my mom,” Virginia says. “It started there.”

As he supported Virginia through her master’s program, John decided he also wanted to get a master’s degree in education. According to Virginia, he had burned a lot of bridges at Cal Poly, assuming that college was in the past — hence Robert Mott’s reluctance to endorse John as both a coach and a match for Virginia.

Mott’s warning aside, the couple married in 1959, and John continued his Cal Poly education.

“I don’t remember John ever saying, ‘Will you marry me?’ But he did say that I was the type of girl he wanted to marry,” says Virginia. “He kept showing up.”

Back on campus after his major career setback, John dove into the Learn by Doing part of his master’s program, taking student teaching and student coaching opportunities wherever he could around the Central Coast. Never much for formal studying, he thrived instead on hands-on learning.

“Some people learn by example and other people learn by participating,” says Virginia. “He learned by participating.”

In those days, coaches had to be teachers first. John’s first job was as a junior high school PE teacher in Orcutt. Virginia, already teaching there, had a sacrifice to make: due to the school district’s no-spouse employment policy, she had to leave the school and find a job teaching at Santa Maria High School.

In his spare time, John attended football coaching conferences, networking to try to land a coaching gig.

“He said, ‘Someday, Virginia, football is gonna support us,’ and I laughed like hell,” Virginia said.

Madden (right) with teammate and future Hall of Fame NFL general manager Bobby Beathard at commencement in 1959. Courtesy of Christine Beathard

The next year, John managed to land his first formal coaching job at Allan Hancock College in Santa Maria. When John started at Hancock, Virginia again had to leave her job in town and returned to Orcutt.

At Hancock, John started as an assistant coach, getting promoted to head coach in 1962 and leading the team to a 12-6 record over the next two seasons. After the 1963 season ended, John got a new opportunity at San Diego State University, where he served as a defensive assistant coach.

While serving as assistant coach, rumors that head coach Don Coryell was moving on got John fired up for another head coaching job. When Coryell decided not to leave after all, John began actively looking for other opportunities to advance elsewhere.

That’s when he got a call from John Rauch, head coach of the Oakland Raiders. He and Raiders operations head Al Davis offered John the job of linebacker coach with a starting salary of $12,000, a 15 percent pay cut from his San Diego State job.

John and Virginia moved from San Diego to the East Bay on the 4th of July, 1967, and Virginia got a job teaching in the local school district to supplement their income. By that time, the couple had two young boys, Mike and Joe. John, scouting the area before the family moved, picked a house by counting how many tricycles he could see in the neighboring front yards.

“It was a neighborhood just full of kids,” Virginia said.

In the locker room at UC Berkeley not long after retiring from coaching, Madden advises the Cal Bears on a winning strategy. MediaNews Group via Getty Images

On Saturdays before game days, John would drive the family car into Oakland for pre-game practice and stay the night. Sunday mornings, Virginia and the boys would ride to the stadium with a neighbor who had season tickets to watch the game, and then the boys would go home with the neighbor while Virginia and John stayed for the post-game celebrations.

In his first season with the Raiders, John helped take the team to Super Bowl II. He took over as head coach in 1969, the league’s youngest head coach at the time.

Mike recalls getting deeper into football discussions with his dad as he got older and became more of a fan of the game.

“He would clue me in on the draft every season,” Mike said. “The draft for a coach is like Christmas for a kid. He would tell me about these players he was excited about, Lester Hayes and Henry Lawrence, and how he was looking forward to seeing them play and become the next great wave of Raider players.”

Over an unbroken streak of 10 winning seasons, John led the team to the AFC Championship game eight times, just one tantalizing game away from a trip to the Super Bowl. To this day, he is the head coach with the most wins in Raiders history and the head coach with the highest win percentage in NFL history.

Madden and Raiders quarterback Daryle Lamonica strategizing on the sidelines during a game against Washington. Bettmann via Getty Images

During those years, Virginia was the Raiders’ most devoted — and passionate — fan.

“I loved those games where we’d win 60 to 5 or 6. I like to win and I like to win big,” she said.

She recalls a moment in the stadium tunnel after a rare loss, when the wife of an assistant coach told her, “Well, you can’t win ‘em all.”

“That always pissed me off,” says Virginia, “I told her, ‘Yes, you can. And I expect to.’”

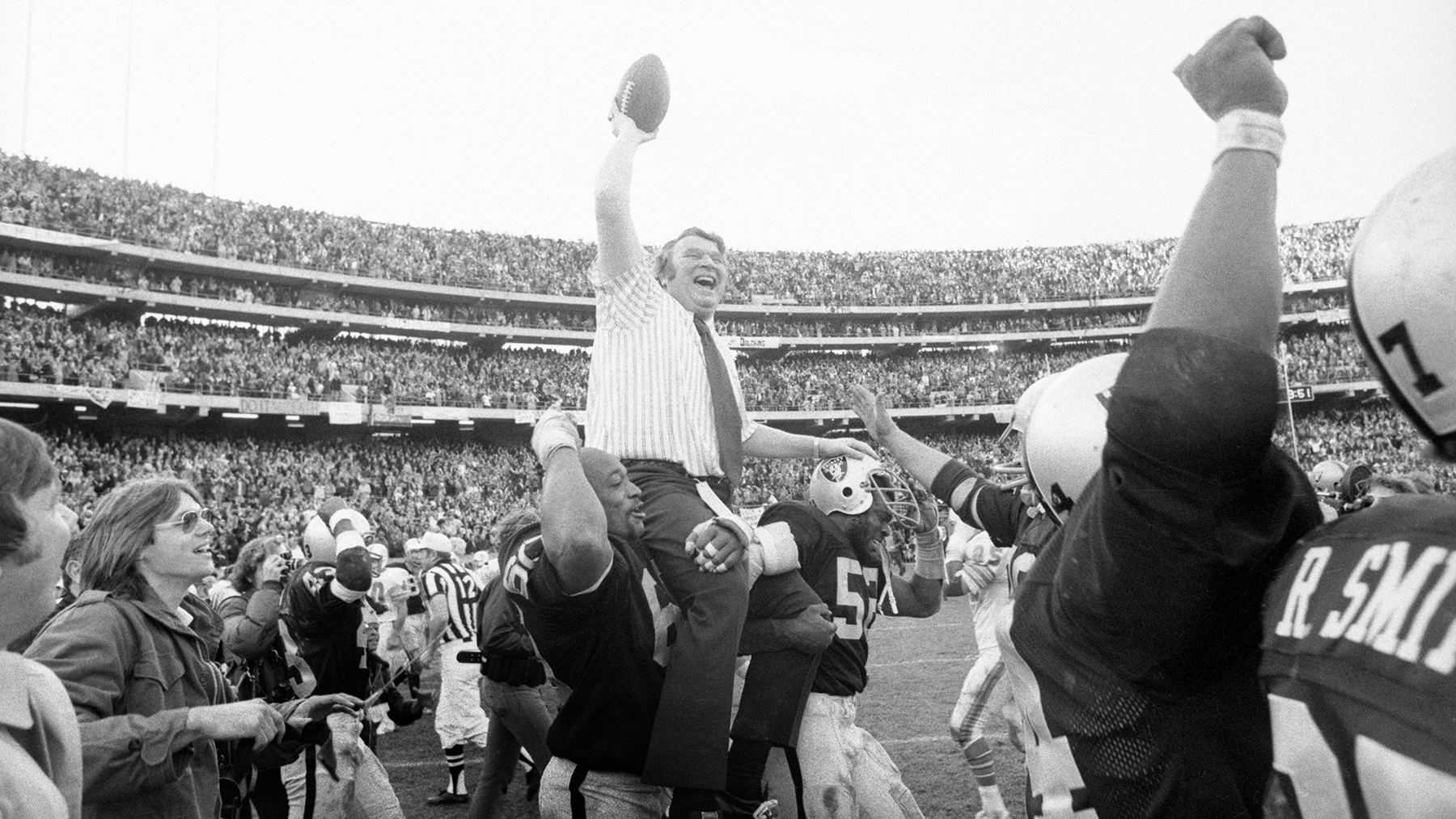

John’s outstanding run as head coach culminated in Super Bowl XI in January 1977, when the Raiders faced off against the Minnesota Vikings.

Mike, then a teen, recalls John joining the family in their hotel room after a practice just before the big game.

“Dad sits down and says, ‘We’re gonna kill ‘em,’” Mike says. “I said, ‘Dad, don’t jinx it!’ But he told me, ‘Not a single ball touched the ground in practice today. We’re sharp. We’re ready.’ And sure enough, they went out there and killed ‘em.”

For the Madden family, the Super Bowl win was personal.

“We’d been along for the ride too — we weren’t just watching him, we’d been at those games and in the stadium,” says Mike. “We’d been dragged through it with him, so we weren’t just happy for him, we felt happy for ourselves.”

After two more winning seasons, John retired from coaching in 1979 due to health problems.

Madden (right) in the broadcast booth with longtime partner Pat Summerall. Focus on Sport via Getty Images

“He had a bleeding ulcer, and after games he would be in the locker room just in pain,” says Virginia. “Finally I told him, ‘John, we don’t need football, we need you.’ I think that helped him realize that there was more to life than football.”

When he retired at age 42, John was faced with the same dilemma he had nearly 20 years earlier: his career had ended, and he didn’t know what he would do next.

So, just as he did back then, he got to work. He started writing a column on football for the local paper, and he was invited to teach a class at the University of California on how to watch football, teaching the uninitiated how to understand and appreciate the intricacies of the game.

Then CBS called him, offering a contract to serve as a color commentator for six games. John wasn’t sure, and asked if he could record a dummy game first and see how it went. Watching the tape with his family later, Virginia advised him that he needed to talk more, even when there wasn’t anything interesting happening on the field.

John took the six-game contract, which turned into a season-long stint. By 1981, CBS had paired John with Pat Summerall as the league’s top color commentary team. Football fans enjoyed his in-depth analysis from years inside the game, and casual viewers loved his eager, jolly persona and the many detours his commentary took from the game itself.

“He was exactly the way he appeared,” says Virginia. “Fun-loving, loved to laugh.”

By John’s third year of broadcasting, he was the official voice of the Super Bowl, was invited to guest host “Saturday Night Live,” and was the star of a national Miller Lite TV ad campaign. At one point in his broadcasting career, he was paid more to call games than any quarterback in the league was paid to play them.

Mike remembers seeing his dad one afternoon on the cover of TV Guide, and it occurred to him that American culture is not always kind to its stars.

“I told Mom, ‘We’ve gotta get ready, nobody stays on top as long as they want to,’” says Mike. “She said, ‘Your dad is not a flash in the pan. Your dad has earned this, and he’s gonna stay on top as long as he wants to!’ And he stayed at the top of that field for 25 or 30 years.”

Madden receives his Hall of Fame ring at his 2006 induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Kirby Lee via Getty Images

From the time he first entered the broadcasting booth in 1979 to his retirement in 2009, John earned 16 Emmy Awards; called 11 Super Bowls; wrote five books about life and football; lent his name, voice and football expertise to the development of EA Sports’ best-selling video game franchise; and even appeared as himself in two major Hollywood films. He became a charter member of Cal Poly’s Athletics Hall of Fame in 1987.

In 2006, he fulfilled a lifelong dream when he was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

“When he was inducted into the Hall of Fame, he was just over the moon,” Mike says.

But not everything was about football. In 1988, John launched Madden Charities, serving the Bay Area through a variety of projects: funding for youth activity centers, food banks and local schools; supporting diabetes, cancer and heart disease research; and fundraising for the Special Olympics.

“I didn’t realize until after he passed the impact he had on so many different lives,” says Virginia. “The letters I’ve received from the people he helped are amazing. He was always caring and giving.”

Memorabilia from Madden’s career at their home, including a bronze bust of John and his Super Bowl Championship trophy.

During the last year of his life, Madden discovered a new opportunity to serve both his local community in Oakland and his alma mater. After attending one of his grandson’s football away games early last year, John skipped his usual post-game analysis with the family to focus on the lack of resources he saw at the hosting school.

“He started brainstorming what he could do for the kids at that school, and then it became, ‘What can we do for kids in the greater Oakland schools?’” Mike said.

By February of 2021, the Maddens had launched a scholarship program that funds Cal Poly tuition for graduating seniors from 12 Oakland area high schools. The first six students received scholarships in the spring of that year. Five more join the incoming Cal Poly class this fall.

“He liked that program — it was on his mind all the time,” says Mike. “He thought a pipeline from Oakland to San Luis Obispo would be a good thing.”

Once a football player at loose ends after an early-career setback, John Madden’s tireless dedication to continually learning and doing, care for his family and loved ones, and willingness to get back in the game ensure his legacy will live on in the memories of millions of football fans around the world, in the people he touched through his charities, in his local community, at his alma mater, and in the hearts of the family that shared his long and winding journey.

On a recent day at his old broadcasting studio, Virginia’s upper lip trembled and her eyes filled with tears as she remembered her larger-than-life spouse, summing up him and their life together in just a sentence.

“He was just the kindest man ever, and I miss him terribly.”

Introducing the John Madden Football Center

Cal Poly’s football program is about to get a major upgrade with the John Madden Football Center, thanks to a lead gift from the Madden family.

The John Madden Football Center will be a $30 million, two-story, 30,000-square-foot football facility in the south end of Spanos Stadium, just beyond the end zone and extending toward the Mustang Memorial Plaza on California Blvd. The building will feature a first floor focused on the physical development of the team, including a locker room, strength and conditioning and sports medicine facilities, while the second floor will provide space for team meeting rooms, position breakout rooms, student-athlete nutrition and lounge, and coaches offices.

Rendering of John Madden Football Center. Courtesy of Ten Over Studio

“A building like this takes the football program to new heights in regards to what we can do to develop our players, both mentally and physically,” said Head Coach Beau Baldwin. “It shows that we’re not just an incredible university with a great academic history, but also that we’re committed to building a championship-level football program.”

John Madden and his son Mike met frequently with President Jeffrey D. Armstrong, Baldwin and Mustang Athletics leadership to develop plans for the new center.

“As we planned the facility, Coach Madden was focused first and foremost on the health, well-being and overall experience of football players,” Armstrong said. “This will be a facility for our student-athletes designed and planned by the best coaches.”

“We had the opportunity to watch a few football games with John, and it was amazing to listen to him talk about the game. After all those years as a commentator, deep down he was still a coach first,” said Baldwin. “Ultimately, as a coach you’re a teacher, and he wanted to do something special to really help our players develop.”

Mike Madden proposed the idea for the facility to his dad after seeing similar football centers on other university campuses and noting the investments being made by Big Sky Conference competitors like UC Davis, Montana and Weber State in similar facilities.

“Dad always wanted to support Cal Poly football and help it get back to its glory days,” said Madden. “He thought, and we all think, that this will be a needle-mover for the future of Cal Poly football, and we’re all proud to be involved.”