When students Lacey Barnes and Emma Bowman unearthed a small metal figurine from the thick clay soil on the Pecho Coast overlooking the Pacific Ocean, their imaginations went wild. It looked like a child’s toy, possibly a firefighter with a hat and a crude steering wheel meant to sit atop a red truck. Could this be a tangible link to the family who lived on this land nearly a century ago?

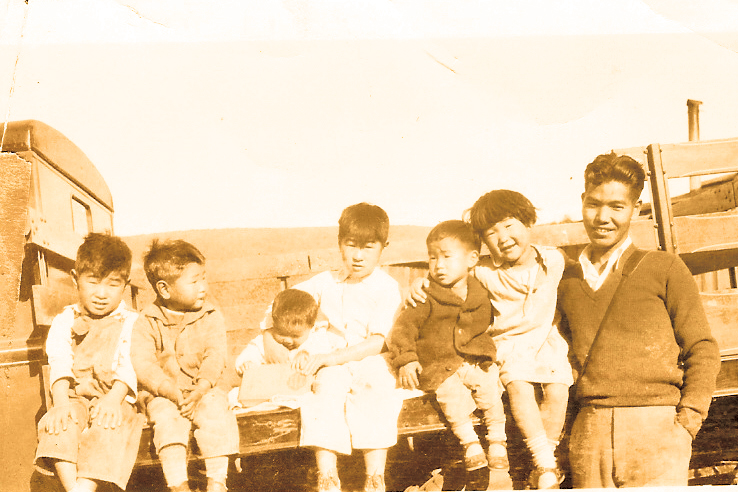

When the budding archaeologists showed the figure to Irene and Grace Yoshida, the group rejoiced. It seemed the toy could have belonged to Charles Yoshida — Grace and Irene’s father — who lived on the farmstead with his parents and nine siblings between 1928 and 1936.

But the discovery, like everything found in the soil that day, eventually felt bittersweet. The family’s toys, precious dishware, tools and more were left behind, and the Yoshida family was eventually forced into an incarceration camp in 1942 for Japanese Americans in Jerome, Arkansas. The family was later incarcerated at Tule Lake in Northern California from 1943 to 1945. The Pecho property in California was sold, their home was destroyed, and they couldn’t return — until recently.

In collaboration with PG&E, Cal Poly anthropology and geography students, faculty and alumni excavated parts of land near Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant to better understand the community of seven families, including the Yoshidas, who lived on the windswept hillside. Over four days in May, students honed their archaeology field work skills while 33 members of the Yoshida family — ages 3 to 77 — reconnected with their ancestral home.

Professor Terry Jones shares insights on the excavation with members of the Yoshida family.

“It was an opportunity for multiple generations to learn and reflect on one single period of time, for my dad’s and his siblings’ stories to come alive,” said Grace Yoshida. “It was when the family was forced to go, leaving behind their farm equipment, horses, home and fields — a time that is hard to imagine without physically experiencing the location.”

The personal connection of the Yoshida family reminiscing at the dig site — just one or two generations removed from those who lived there — taught a lesson on how anthropological work can reunite the past with the present.

“I think everybody recognized the importance of the situation, and I know that we were all deeply affected by our interaction with the Yoshida family,” anthropology professor Terry Jones said. “In 45 years of doing this, I’ve only had a few moments in my career — the best moments — where something affected me so strongly.”

The Archaeology Field Methods Course

The excavation was the culmination of ANT 310: Archaeological Field Methods, co-taught by Jones and geography professor Andrew Fricker. The course taught 25 students how to combine real-world excavation techniques with a detailed digital mapping process. It also fulfilled the hands-on field school experience required for a career in archaeology.

“The only real way to teach students how to conduct excavations is to put them in the trenches, hand ’em the tools, and give them the Learn by Doing experience,” Jones said. He has partnered with PG&E’s cultural resource managers for 20 years to give students field work opportunities that preserve important pieces of history on Diablo Canyon land.

To prepare for the dig, students downloaded historical photographs taken by the Army Air Corps in the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s and assessed the land’s topography with PG&E’s laser scanning data. Any flat spots could be a clue that a structure may have stood there. Students also learned from the oral histories that members of the Yoshida family recorded with PG&E over the years, including interviews with Charles Yoshida before he passed away in 2020.

Fricker taught students to use GPS data, geographic information systems (GIS) programs and a drone with a multi-spectrum camera that mapped the site three times: before, during and after the dig. A precise map helped the archaeology team make the most of the limited time it had on property typically closed to the public.

“All of that is traditionally done with a compass, tape and paper maps. My role was to show the students how to make that all digital,” Fricker said. “It’s very clear the skills that [students] need are changing rapidly, and they include all these technologies.”

A Learn by Doing Experience

On Memorial Day weekend, vanloads of students, faculty, alumni volunteers and Yoshida family members drove out to the farmstead’s original site for the first time. Native monitor Mona Tucker, a member of the yak titʸu titʸu yak tiłhini Northern Chumash Tribe, joined the team to offer guidance in case they encountered any Native artifacts.

Before the work began, Tucker spoke passionately about the concept of home, telling the group that she respected the land as the home of the Yoshida family as much as the Chumash, who have more than 10,000 years of documented history on the Central Coast.

“We could feel free to share our family background, culture and traditions, too,” said Irene Yoshida of her conversations with Tucker. “We enjoyed the exchange as a two-way street.”

Jones divided the land into a grid of squares, or transects, that correlated to a central mapping point or datum. After walking the site to spot any artifacts on the surface, the students formed teams and began digging in several locations, including one spot the archaeologists thought might be the home’s refuse disposal site. Each team dug up their transect to a depth of 10 centimeters, then 20. Some members of the Yoshida family even jumped in the trenches to dig alongside students with trowels.

Students poured excavated material onto a tarp and used shaker screens to separate artifacts from dirt. Over hours of work, the team unearthed a staggering number of artifacts, including pieces of Japanese teacups, platters and bowls painted with an intricate blue and white pattern.

“I’ve been puzzled by how much of this broken ceramic we found, and I think it could have something to do with those 10 kids, to tell you the truth,” Jones said. “It just seemed like a large quantity of beautiful pottery was being broken. You don’t see that much typically at sites, but they were setting a beautiful table.”

The team discovered more fragments of glass jars, metal parts from gates, coins and toy marbles. There was also a wealth of beef bones, red abalone and Pismo clam shells, indicating what the family may have eaten regularly.

“My dad, Charles, would have loved to attend the excavation of his childhood home,” said Irene Yoshida. “He would have been delighted to revisit, remember, and hold beloved belongings from his family. Dad would have turned 100 this year, so the dig is like we received a special birthday present from PG&E and Cal Poly!”

The day of the dig was full of anticipation for student Lacey Barnes. She switched her major from aerospace engineering to anthropology to focus on archaeology. The weekend tested if she would thrive doing the strenuous field work her dream job demanded.

“I had to plan my whole life around this weekend for a little while, but it was so worth it,” she said. “I really enjoy the work; I love doing it. I felt so accomplished every day.

“I think the emotional aspect made it so much more meaningful, especially for a first excavation, but it’s really motivated me for future ones.”

On the site, Barnes and her fellow Mustangs leaned on several Cal Poly anthropology graduates — now employed as professional archaeologists and cultural resource managers — who volunteered as crew chiefs. Emma Cook (Anthropology and Geography ’17) was one of four alumni who helped supervise students as they practiced key excavation techniques, documented artifacts and collected data that fit Jones’ research design.

“The opportunities that [we are] providing are as good, if not better, than any place else in California, largely because we have this great relationship with PG&E and we’ve been able to investigate really fascinating sites,” said Jones. “I suspect that there’s probably no place else in California where anybody got an experience quite like this.”

Reconnecting to the Land

For more than a decade before the excavation, members of the Yoshida family could only look at their former homestead from a trail’s edge.

“It was out of reach, yet appeared so close,” said Grace Yoshida. “Many Japanese American families could only look into the distance and see the iconic landmarks from the Point Buchon trail.”

To Grace and Irene, being on the farmstead site with so many family members — from Aunt Betsy, the youngest sibling in the original Yoshida family; to Kayden, a three-year-old great-great-granddaughter — was an essential opportunity to pass down family history to new generations.

Dylan, Charles Yoshida’s grandson, said he was amazed that others were taking an interest in his family’s history. “It would have been forgotten if the younger people weren’t there,” he said. “[I] just didn’t want the knowledge to be lost with this generation.”

For a few of Cal Poly’s team members, the experience mirrored their own family history.

“My maternal grandparents were in the internment camps in World War II,” said Fricker. “I see a lot of my own family in [the Yoshidas]. They went through this really traumatic experience. The difference is that their experience of being displaced was at Diablo Canyon, so it’s hard for them to get back there.”

The Yoshida family created painted rocks and origami cranes that were buried in the soil at the end of the excavation as a tribute to their ancestors who lived on the land.

At the conclusion of the dig, the Yoshidas made a gesture to ensure their family could stay connected to the land forever. Family members brought origami paper cranes, which represent longevity, and painted rocks for three generations of family who lived on the property: grandfather Yaemon Yoshida, parents Tomoichi and Kikuno and children Masao, Charles, Inez, Thomas, Edward, Rose, Margaret, Byron, Paul and Sandra. One side of the rock had each person’s name in Japanese, the other side had their name in English. As the students were backfilling the trenches, the Yoshidas buried the rocks and cranes under the soil, signifying a return home.

“I wiped away a tear more than once, and the students did too,” Jones said.

“It was such a sweet way of them asserting themselves back on this land that they got pushed off of,” said Barnes. “I was so honored to be a steward of that in any way. It was so incredibly emotional. It made it feel larger than just a senior project or just an excavation. I don’t know if I’ll have an experience like that ever again.”

A Senior Project

Anthropology and geography student Annie Pagel looks for artifacts using a shaker screen. Her collaborative senior project aims to bring the family’s history to light next year.

Students aren’t done with what they found at the excavation site. The team carried dozens of buckets with artifacts and soil back to campus. In winter, students will wet screen the loads of dirt, clean all the artifacts, sort and catalog everything as part of an Archaeological Laboratory Methods course.

Students Barnes, Annie Pagel and Emma Bowman will then work on a collaborative senior project to transform the material and new interviews with Yoshida family members into an historical exhibit that will be open to the public in 2025. The Yoshidas plan to make another trek back to the Central Coast for its grand opening.

“My hope is that the Cal Poly archaeology exhibit on Pecho will beckon more Japanese and other immigrant families to learn more about their roots,” said Irene Yoshida. “I am forever grateful to PG&E for hosting the collaboration with Cal Poly, to manifest our Yoshida family’s history more visibly and deeply.”

The Yoshida Family

Tomoichi and Kikuno Yoshida met and married in Japan before immigrating to the United States. They lived in Guadalupe for a short period before settling on the Pecho Coast near Point Buchon in 1928. They eventually had 10 children while living on the farmstead, making their living growing bush peas, Brussels sprouts, artichokes and lettuce. The Yoshidas raised chickens, and they ate a variety of local shellfish.

After living on the Point Buchon farmstead for eight years, the family moved to a nearby home near Coon Creek. The Yoshidas were forced off the land in 1942 when Executive Order 9066 led to the mandatory removal of all Japanese and Japanese Americans. The family eventually had two more children, including one born as the family was moving to the incarceration camp in Jerome, Arkansas.

After the family’s release from the Tule Lake incarceration camp in 1945, they moved onto the property of a family friend in Auburn, and stayed in their unfinished barn. Hearing of agricultural work opportunities in the Monterey Bay area of California’s Central Coast, they moved to Watsonville to sharecrop strawberries.

Charles, who was the second oldest of the Yoshida children, returned to the Pecho Coast in July 2008 to hike the newly-opened Point Buchon Trail with his adult children. A park ranger connected Charles with Sally Krenn, a PG&E biologist. Because of Krenn’s initiative, Charles and his family members were permitted to visit the Pecho Coast for two pilgrimages: in October 2009 with 20 family members and in April 2013 with 13 family members to see a new trail information sign at Windy Point, titled “Japanese Farmers – Part of Pecho History.” The sign featured information about the Yoshida family and photos of Charles and his siblings.

The excavation in 2024 was the largest gathering of the Yoshida family at the site of their ancestral home in Pecho. Among the family members were two Cal Poly alumni: Jenna Bagley (Business Administration ’08, M.S. Accounting ’09), the granddaughter of Inez (Yoshida) Hashimoto, and her husband Justin (Mechanical Engineering ’09), who met while attending Cal Poly. They brought their two young daughters to the excavation to learn about their great-grandmother, Inez, the third oldest child in the family.

“I always knew that my grandmother once lived in Montaña de Oro, but the significance of this didn’t really hit me until our recent visit,” Jenna said. “My grandmother talked very little of her childhood growing up (especially her time in the camps), but I do recall her mentioning that she had pleasant memories in their home. It was mind-blowing to see the site where she and her many siblings lived so many years ago — to picture how they worked and played on that spot.”

“The girls were very excited to see some of the pieces of pottery and toys that came out of the ground,” she said of her daughters. “It was so important to connect with extended family that we don’t see often. When they are older, I hope that we can return again and hopefully discover more artifacts of my grandma’s past.”