Questions and Answers

Can 'The Martian' Get Us to Mars?

Media researcher David Kirby explores the intersection of science fiction and real life space exploration.

By Gabby Ferreira

Share this article:

A still from the movie “The Martian,” in which Matt Damon portrays an astronaut trying to survive on Mars.

Humans have been making movies about space since before astronaut was a profession. David Kirby, chair of the Interdisciplinary Studies Department and director of the Science, Technology and Society Program, examines the interactions between science and entertainment media in all its forms including movies, television shows, graphic novels, comic books and video games. Kirby sat down with Cal Poly Magazine to talk about the influence of movies on space exploration and vice versa.

HOW DO OUR CONCEPTS OF OUTER SPACE INFLUENCE HOW MOVIES TAKE SHAPE?

A lot of what I talk about as a science communicator is the idea that space travel is all about exceeding limitations.

There are physical limits of gravity and the human body, but the biggest limitation is convincing people that this is worth doing. Because it’s not inherently clear to people that spending their tax dollars on helping people go into outer space is worth doing.

When you want to generate interest in a technology, whether it’s space-related or something else, you need to do three things: You need to convince people that it can work, that they actually really need it and that it’s safe.

There’s a term I coined called “diegetic prototype” that applies to technologies that only exist in fictional worlds. These diegetic prototypes show audiences how future technologies can be used in ways that could make sense in our world.

About every 20 years, you see iterations of space-related diegetic prototypes in movies.

A great example of this is “Destination Moon,” a movie that came out in 1950 — just as the Cold War began in earnest. That film played a major role in convincing the public that we needed to get to the moon.

The biggest reason the movie gave for space exploration was the idea that the moon would be a big military problem in the Cold War. There’s a scene where a general gets up to talk to all the funders of the mission and says, “We’ve gotta do it, ‘cause the first country that reaches the moon can throw nuclear weapons at the Earth.”

And then a funder gets up and says, “We’ve gotta do it!” And that’s aimed at the public, this message of: If we don’t get to the moon, the Russians will.

They’re using the power of movies to say, “This can work, and we need to do it.”

WHAT IS FILM’S ROLE IN THE TRAJECTORY OF SPACE EXPLORATION? HOW HAVE MOVIES SHAPED PUBLIC OPINION ABOUT GOING TO SPACE?

In the 1950s, filmmakers used defense as the main reason for going to space and getting to the moon. It’s a matter of national pride.

But after the Apollo missions, it becomes a job. If you look at space films in the ’70s and early ’80s, space travel looks boring — intentionally. In the film, “Alien,” the characters are blue-collar workers on a spaceship that just happens to be where they work.

The next film that really gets the public jazzed about space is “Apollo 13” in 1995. This film, about a real-life mission, makes NASA look amazing. Everyone in the movie pulls together; the characters use American ingenuity to bring the boys home. That actually spiked great interest in NASA and in funding space endeavors.

Around the year 2000, when the Mars rovers start taking off, you get films like “Mission to Mars,” which had NASA consultants. The idea is that the next thing NASA wants to fund are trips to Mars, and that’s where the diegetic prototype comes in: movie audiences see a colony on Mars and they get reasoning in the movie that explains why we need a colony on Mars — mainly environmental impacts and safety.

At that time, NASA was actually posting images online that the Mars rovers had taken. That was the most-visited website ever at the time. The rovers generated ideas for these films, which in turn generated more interest in going to Mars.

Then you have the post-space shuttle era. In 2011, NASA’s space shuttle fleet was retired. And the challenge became: How do you get people excited about space again when this big program is gone?

One of the things filmmakers do in this era is convince people that there’s still a lot we can do in space for the public good, like cure climate change. But one of the biggest things is generating inspiration and wonder. It’s convincing people that being a human in a society is not just about living and surviving, it’s about reaching for the stars.

You get films like “Interstellar” and “The Martian.” These films are about trying to generate that sense of wonder. The underlying question they ask is, “Wouldn’t it be amazing if we were able to do this type of space travel?”

In turn, that generates new interest. With “The Martian,” NASA essentially said, “Hey, this is exactly the type of space work we want people to think we should be doing.”

And it does make NASA look amazing. The scientists in these movies are the heroes. Matt Damon as an astronaut is totally heroic. It’s all about the power of science, and that gives NASA a big boost, with people wearing their NASA shirts and perceiving NASA as this cool thing to be part of.

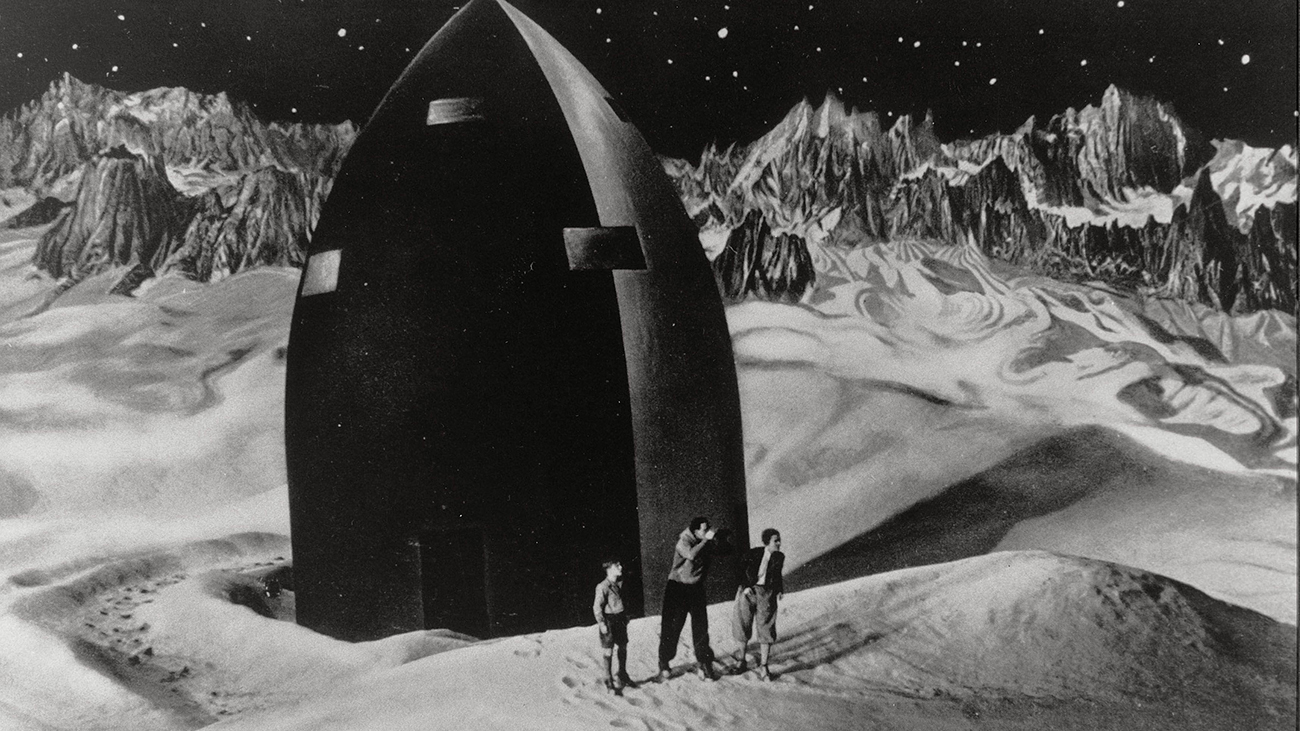

A still from “Frau im Mond,” Fritz Lang’s 1929 film that originated the modern-day launch countdown.

WHAT’S THE EARLIEST EXAMPLE OF MOVIES INFLUENCING THE DRIVE FOR SPACE EXPLORATION?

In the mid-1920s, a German director named Fritz Lang, who most people know from his movie “Metropolis,” wanted to make a movie about going into outer space. He wanted it to be the most scientifically-accurate movie about this ever made, because movies about space at the time were really fanciful with no sense of scientific accuracy at all.

So, Lang hired scientists from the German Rocket Society — a group that was very influential in getting people interested in going to space — to help with the rocket scenes in the movie. In particular, he hired Hermann Oberth and Willy Ley, who eventually became very influential in the American space program. Oberth and Ley saw this as an amazing opportunity to promote rocketry.

At the time, the society was having a hard time getting funding because they had to convince people it was worth doing. As they saw it, working with Lang, who was incredibly famous, was a perfect opportunity to show people what rocket science could actually do. And Lang, for his part, basically left them alone. They made the rocket scenes as scientifically accurate as they could.

The resulting movie, “Frau im Mond” (“Woman in the Moon”), actually invented the countdown. Before, rocket scientists counted upward. Lang said “No, no, no. The audience won’t know when to stop, so we have to go from 10 down to zero.”

This movie ultimately led to the German Rocket Society getting some funding. Unfortunately, it came from the German military, but that’s the power of cinema.

"One of the things filmmakers do in this era is convince people that being a human in a society is not just about living and surviving, it’s about reaching for the stars."

DAVID KIRBY

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO MAKE MOVIES ABOUT SPACE AND TO ACCURATELY COMMUNICATE SCIENTIFIC IDEAS ABOUT SPACE EXPLORATION?

One of the main ways that space movies are successful is because they have that scientific realism attached to them so that the audience can buy into it and say, “Yes, I see that we can actually do that.”

In science communication, you learn thatfacts are not the most important thing in getting people to care. It’s what science means to people that gets them to change their minds.

Science communicators have to try and shape that and give people a positive reason for why they want to do something. With space films, we need to show them why we want to support this.

Here’s an example. When “Armageddon” and “Deep Impact” came out in the late ’90s, they actually had major impacts on policies in the U.S. and in the U.K. because those movies convinced the public that an asteroid hitting the Earth was a danger that we needed to worry about.

Before those movies came out, everyone thought that idea was silly. But the scientists who worked on those films, especially “Deep Impact,” talked about trying to remove the silliness factor. So then you have congresspeople on the floor of the Capitol, and members of Parliament talking about these movies, and it resulted, at least in the U.S., in more funding for NASA and NOAA.

Those movies got the public on board. There are a lot of anti-space movements out there. There are a lot of people who bemoan the fact that we’re spending money on going to outer space, when we could spend money solving problems here on Earth.

In some ways, that’s a convincing argument. How can you look at starving people and still say we need to go to outer space? But it’s not always a trade-off.

The inspiration for a lot of the more recent movies about space is the idea that we have to show ourselves that we’re more than just primates stuck on a planet trying to survive, and we should be more than that.

Space is one way that we can transcend the bounds of where we were created, so to speak. I think that it’s important for us to do that, and movies provide a very significant way of showing us that inspiration and wonderment.

Your Next Read

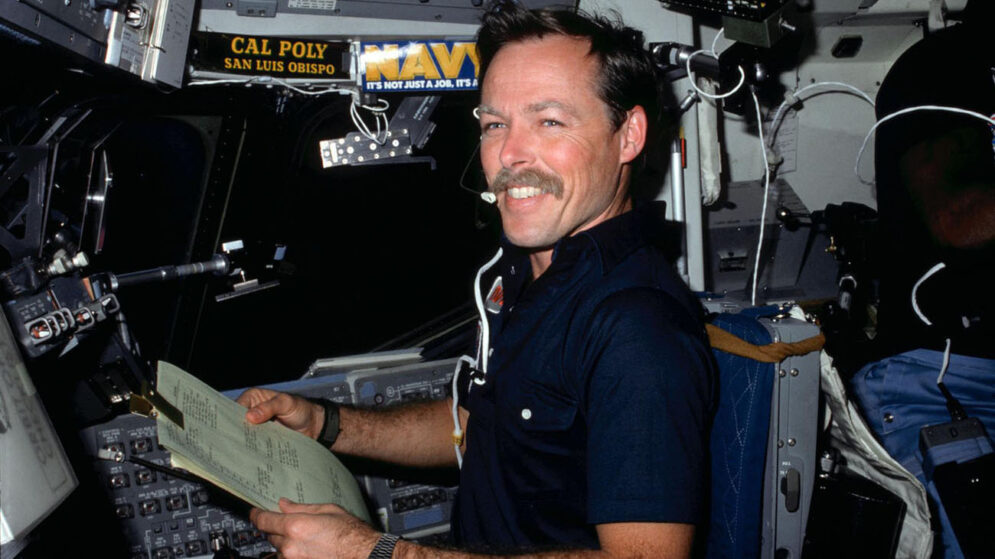

From a childhood in the skies to orbital spaceflight, Cal Poly’s first alumni astronaut used Learn by Doing to carry him ever higher.

Travel the cosmos with an interstellar playlist curated by KCPR’s student music director.