A Legacy in Space

Chasing the Horizon

Meet Peter Siebold and Michael Alsbury, two test pilots whose friendship and careers were intertwined through triumph and tragedy.

By Robyn Kontra Tanner

Share this article:

Scaled Composite’s team of experimental test pilots with White Knight and SpaceShipOne in 2008. From left: Mike Melvill, Brian Binnie, Peter Siebold, Doug Shane, Michael Alsbury and Clint Nichols. Photo by Jim Sugar/Corbis via Getty Images.

When Cal Poly students Peter Siebold (Aerospace Engineering ’01) and Michael Alsbury (Aerospace Engineering ’98) crossed paths, they had no way of knowing their friendship would become more than a decade of mentorship, collaboration and professional triumph. Though Alsbury’s life was tragically cut short, the duo’s shared legacy continues to light the way through the next chapter of commercial space exploration.

Siebold first met Alsbury during a meeting of Cal Poly’s Sigma Gamma Tau honor society for aerospace engineers in the late 1990s. The budding engineers immediately connected.

“I remember thinking, ‘This kid alongside me, he’s going places,’” Siebold said of Alsbury. “He was such an amazing person — just skilled at almost everything he touched.”

Cal Poly turned out to be the launch pad for Siebold and Alsbury. The pair became test pilots and close collaborators at Scaled Composites, an aerospace research and development company located in the Mojave Desert. They worked closely with legendary aircraft designer and fellow Cal Poly alumnus Burt Rutan (Aerospace Engineering ’65), the company’s founder, on boundary-breaking technology that would reshape the aerospace industry.

One of their first projects helped test a new generation of weather sensors that became the backbone of modern weather forecasting. Alsbury served as a test flight engineer on board the aircraft while Siebold was at the controls.

“We’d go fly out over the Atlantic, hunting down thunderstorms during the day and in the middle of the night,” Siebold recalled. “As a young pilot and engineer, seeing the Earth from 50,000 feet was really inspiring. It was really just the beginning of what was to come.”

A few years later, Siebold and Alsbury tackled one of the most revolutionary commercial aerospace projects of the time: SpaceShipOne, which became the first crewed private space flight using an air-launched spacecraft that could land on a conventional runway.

"I think there’s a common misconception that test pilots are cowboys and risk junkies ... A test pilot will push themselves to the limit, but then they know where the boundaries are.”

Peter Siebold, test pilot

Scaled Composites designed and built the carrier aircraft, named White Knight, and the spacecraft from scratch with a novel, rocket-powered propulsion system. Siebold admitted he was daunted by the concept at first.

“I had to put so much faith in [Rutan’s] vision and recognize that he saw something that I just didn’t have the experience to see at the time,” said Siebold. “It was one of the most rewarding programs I’ve had the chance to work on.”

Alsbury contributed as a control room operator, component designer and flight test engineer. Siebold engineered the avionics, navigation and ground control systems. When he piloted test flights of the aircraft, Siebold said the experience provided an unparalleled feedback loop.

The team earned the $10-million Ansari X Prize in 2004, awarded to the first organization to launch a reusable crewed spacecraft into space twice within two weeks. Scaled Composite’s SpaceShipOne test pilot team of Siebold, Brian Binnie and Mike Melvill also earned the Iven C. Kincheloe Award for outstanding accomplishments in flight testing from the Society of Experimental Test Pilots that year.

“I think there’s a common misconception that test pilots are cowboys and risk junkies,” said Siebold. “The core science behind flight testing is risk mitigation. We try and take baby steps. We don’t go as fast and as high as you possibly can on the very first flight. A test pilot will push themselves to the limit, but then they know where the boundaries are.”

In 2008, Alsbury and Siebold began work on SpaceShipTwo, an air-launched spaceplane designed for space tourism in partnership with Virgin Galactic. SpaceShipTwo and its carrier plane, White Knight Two, were twice the size of their predecessors and were designed to take up to eight people, including two pilots, to an altitude of up to 110 kilometers.

Alsbury was part of the test pilot team for both aircraft. Siebold, the chief test pilot for White Knight Two, was at the controls of the aircraft’s maiden flight in 2008 and earned his second Kincheloe Award for the effort the following year. He counts the first flight of SpaceShipTwo in 2010 — a flawless ride he took with Alsbury by his side — as one of the most memorable in his career.

But on Oct. 31, 2014, tragedy struck.

Siebold and Alsbury were co-piloting SpaceShipTwo during a test flight when the spaceplane broke apart high above the Mojave Desert, severely injuring Siebold and killing Alsbury.

The Space Mirror Memorial at the John F. Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex, with Alsbury’s name engraved on the right.

“As a test pilot, you recognize the risks that are being taken: I certainly knew it and Mike knew it as well,” said Siebold, voice shaking as he recalled the memory. “Ultimately, it has deeply affected me, my family, as well as everybody that worked on the program.”

To honor Alsbury’s contributions to the aerospace community, the Astronauts Memorial Foundation etched his name into the Space Mirror Memorial at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex in Florida in 2020. Former NASA astronaut and Virgin Galactic pilot Rick “CJ” Sturckow (Mechanical Engineering ’84) played an important role in helping the foundation update its criteria to include commercial and private astronauts on the memorial.

Alsbury was posthumously awarded Federal Aviation Administration commercial astronaut wings in 2021.

“While he never crossed the formal line considered to be the definition of an astronaut, his contributions to the commercial space effort and space travel are really important,” said Siebold. “It’s an honor to know he will be remembered in that way.”

Alsbury’s widow Michelle Saling (Ecology and Systematic Biology ’98) shared this reflection:

“Mike was a very kind and genuine person. He truly cared about people and really took the time to get to know people and connect in meaningful ways. He made you feel seen and appreciated. He loved spending time with his friends and family and absolutely adored his kids.

“Mike loved sharing his passion for flying with everyone and was eager to take you up for a ride. Mike had an amazing ability to live in the present moment and find joy and humor in every day. My kids and I love him deeply and miss him tremendously.”

How Peter Siebold Met Burt Rutan

Siebold was serving as a teaching assistant in an aircraft design course when the class, including Alsbury, toured major employers in Southern California. In a small conference room at Scaled Composites in the Mojave Desert, Burt Rutan (Aerospace Engineering ’65) posed a loaded question to the group: who wants a job?

The undergraduates were stunned into silence, but at the back of the room, Siebold raised his hand. In a job interview just days after the tour, Rutan candidly stated that he didn’t care if Siebold officially had his degree yet.

“He kind of twisted my arm and convinced me to stop going to school and come join Scaled,” Siebold said. “I joke with today’s interns that I had Scaled’s longest internship in history because I worked four years as an engineer and test pilot before I came back and finished my last two quarters.”

While finishing his last general education courses at Cal Poly, Siebold was still working part time and tackling some major engineering challenges. He admits he began designing the avionics and navigation systems used in the SpaceShipOne program in a lab on campus.

Your Next Read

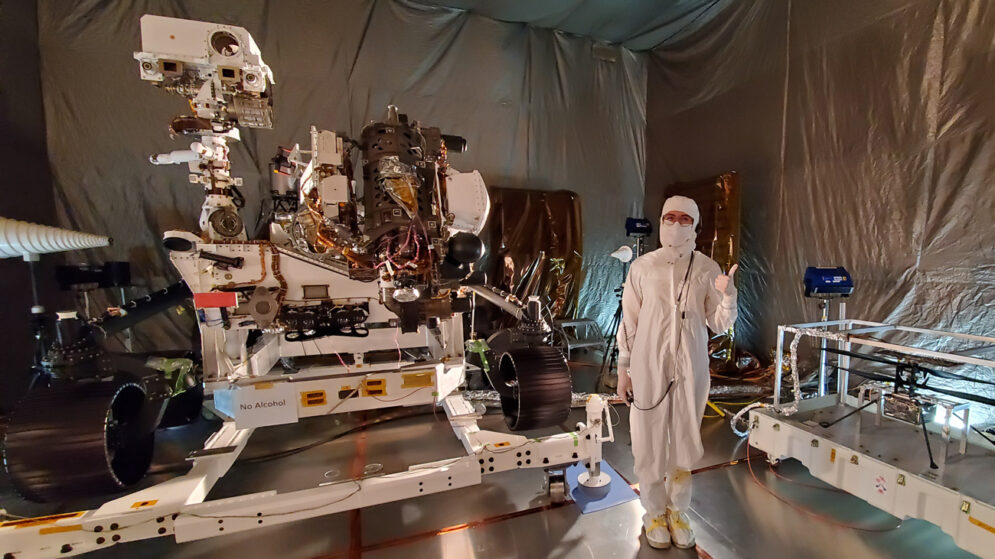

Alumna Christina Hernández has charted new territory — from Mars to distant asteroids — all while inspiring the next generation of Spanish-speaking engineers.

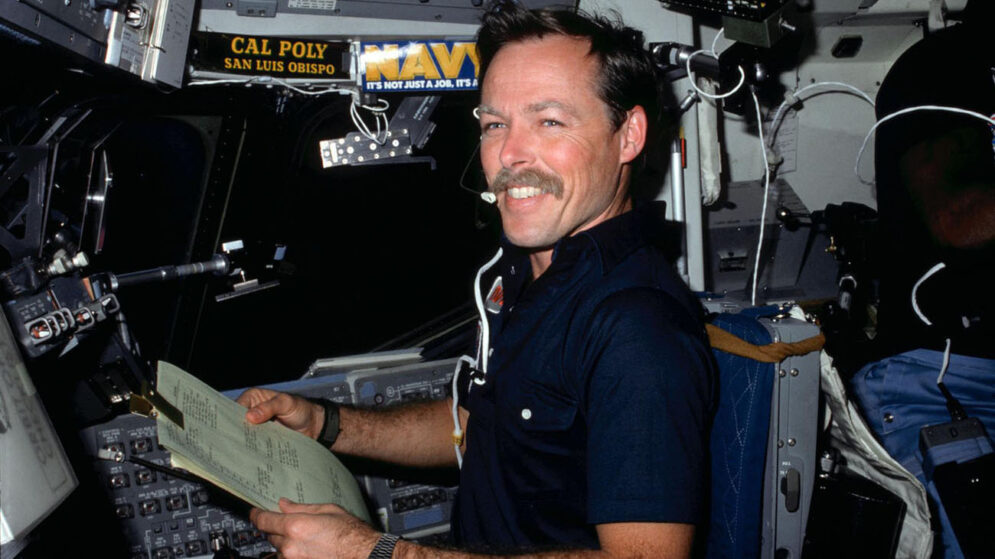

From a childhood in the skies to orbital spaceflight, Cal Poly’s first alumni astronaut used Learn by Doing to carry him ever higher.