Featured

Opportunities in Orbit

Cal Poly’s CubeSat Lab broke barriers. Two decades later, students are still rewriting the story.

By Emily Slater // Photos by Joe Johnston

Video by Matt Yoon and Dylan Head

Share this article:

Aerospace engineers Gretta Thompson (left) and Benjamin Kurtz perform side panel integration on the CubeSat Lab’s latest payload in the clean room.

In July 2006, a Russian rocket lifted off from Kazakhstan, carrying a radical idea: CubeSats — tiny satellites packed with potential. Among them were the first developed at Cal Poly, built to a new standard that changed the rules of who could reach space.

But the rocket never made it to orbit. A malfunction in its combustion chamber caused it to crash back to Earth. Burned satellite fragments were later recovered by farmers and returned to San Luis Obispo in briefcases, a haunting reminder of a mission that ended before it truly began.

“It was a huge blow,” said Roland Coelho (Aerospace Engineering ’12), who helped coordinate Cal Poly’s early launch efforts in Russia. “We had poured everything into those satellites.”

The crash destroyed CubeSats from several U.S. schools, each built to a 10-centimeter cube standard pioneered at Cal Poly. At the time, Russia offered the only viable launch option for student missions. There was no clear path to fly from the U.S., and the high-profile failure exposed that gap.

To many in the aerospace world, CubeSats were still seen as fringe — too small to matter, too risky to trust. But the timing was right for change. Launch vehicles were becoming more efficient. Electronics were shrinking. Cal Poly’s CubeSat Lab helped turn skepticism into possibility, shifting the conversation from theory to orbit and amplifying a movement already taking shape.

More than 20 years later, a new mission from that same lab is preparing for launch at Vandenberg Space Force Base, and it holds a message of its own.

Named SAL-E, the satellite is dedicated to CP1 and CP2, the first CubeSats built at Cal Poly. It’s a tribute to the loss that started it all and the students who never stopped building.

“This satellite is all of us,” said Jess Bleakley, an aerospace engineering senior and the lab’s manager. “It carries everything we’ve put into it — and now it’s going to space.”

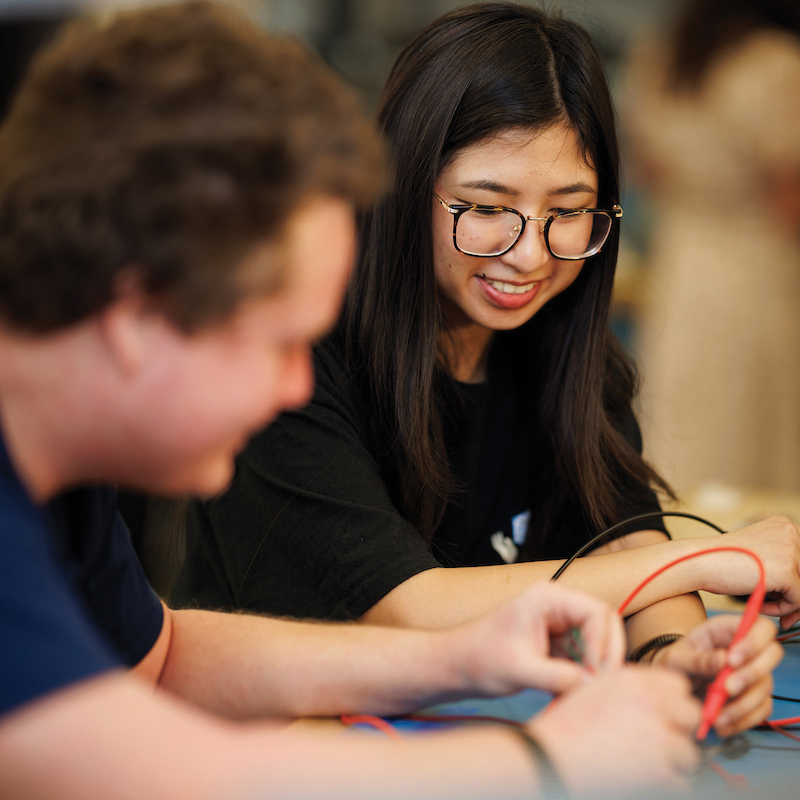

Students at work in the CubeSat Lab in 2024 and 2025.

Engineering the Mission

Berfredd Quezon didn’t expect to lead a space mission before his third year of college. But as mission lead for SAL-E (short for Streamlined Assembled Learning Experiment), the computer engineering major is steering a team through one of the lab’s most ambitious projects.

“It’s definitely been a challenge,” he said. “But it’s also been really exciting.”

SAL-E is expected to launch in early 2026. It will carry two student-designed payloads to test a low-power radio and an open-source chip in orbit.

For many students, SAL-E was their first real exposure to spacecraft. After the pandemic disrupted lab work and slowed projects, the mission offered something essential: a chance to rebuild lost knowledge through shared experience.

“We were all figuring it out together,” Bleakley said.

Inside the CubeSat Lab, the atmosphere is both focused and informal. Students troubleshoot circuits at cluttered benches, track data on whiteboards and reroute tangled cables between blinking test units. A cardboard cutout of aerospace engineering professor Jordi Puig- Suari, co-creator of the CubeSat standard, leans against one wall. Overhead, a stuff ed Yoda looks on — a quiet reminder that patience, creativity and a sense of humor all belong in spaceflight.

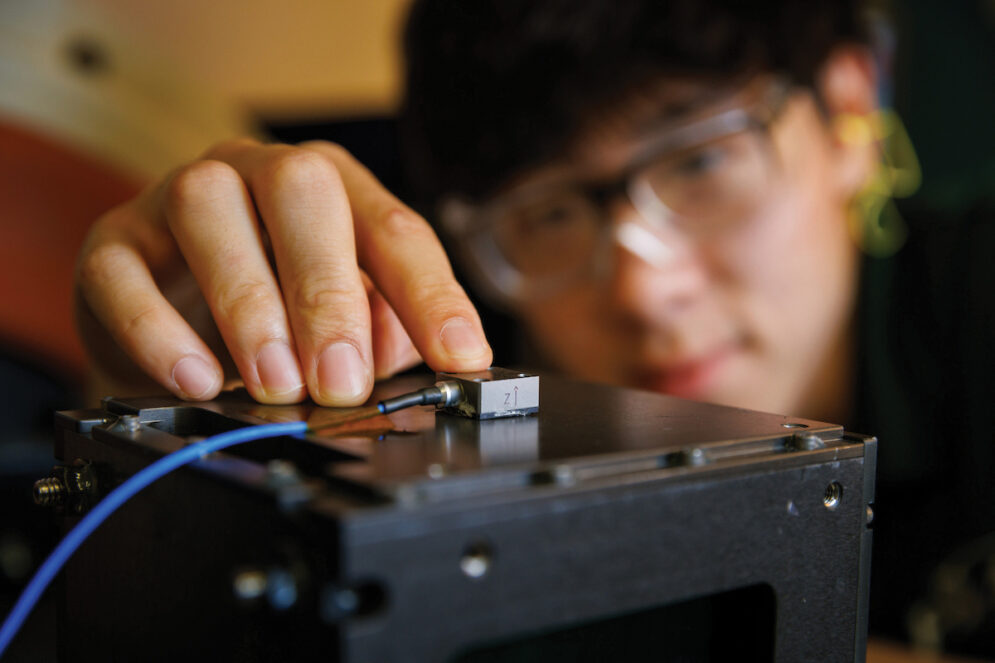

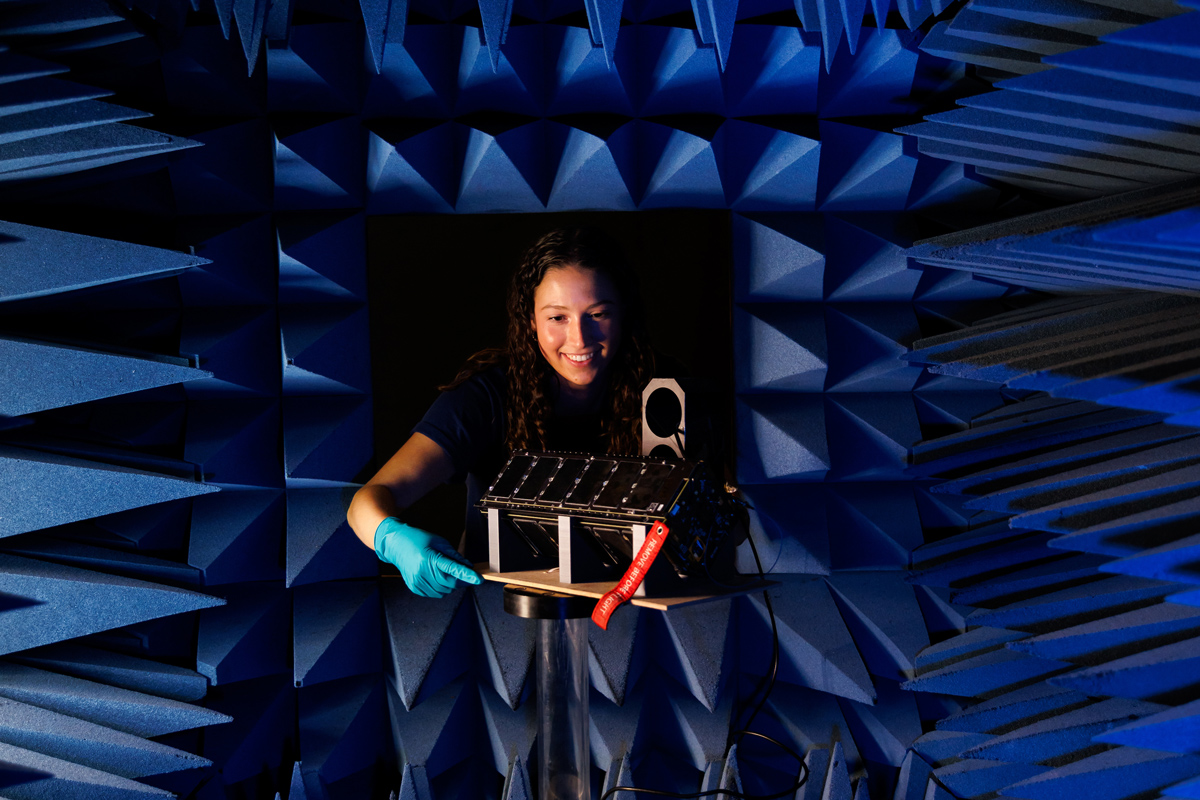

First photo: Aerospace engineer Jacky Hu runs tests on a fixture of a CubeSat in the Vibrations Lab. Second photo: Joshua Tuttobene, who is earning a master’s degree in mechanical engineering, refines the CubeSat’s counterweight in the Mustang 60 Machine Shop. Third photo: Computer engineer Lauren Jones positions the CubeSat payload in an anechoic chamber to tune the circuit board’s dipole antenna.

Each year, about 60 students contribute to the lab, organized into teams such as avionics, operations, software and systems. Together, they help turn concepts into flight-ready hardware — efforts that have produced 12 launched CubeSats. That team-based model has supported SAL-E from design reviews through integration, with students taking ownership not just of the satellite but also of its test systems.

Aerospace engineering student Gretta Thompson, who leads assembly, integration and testing for SAL-E, led the effort to restore the lab’s thermal vacuum chamber and brought on fellow aerospace major Ben Kurtz to help.

“We dug through old procedures and brought the chamber back to life,” Kurtz said. “Now my name’s one of 40 etched onto the counterweight. It’s surreal knowing that’s going to space.”

Elsewhere in the lab, students are working on something even more experimental. AMDROHP (short for Additively Manufactured Deployable Radiator using Oscillating Heat Pipes) will test a new kind of radiator designed to help small satellites manage heat in orbit. The project is part of an ongoing collaboration with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Cal State LA.

Mechanical engineering student Ben Gillette gained experience on SAL-E, building a foundation in engineering and mission design that prepared him to lead AMDROHP and push the team into more advanced systems.

“We’re iterating and learning as students,” Gillette said. “It’s high risk and high reward. If AMDROHP works, it opens the door for a new class of CubeSat missions.”

The satellite is slated to launch aboard a future Voyager Space mission from Cape Canaveral, bound for the International Space Station, where it will be deployed into orbit from a dispenser on board.

This fall, Gillette and Bleakley will share the team’s work on a global stage, presenting a technical paper at the International Astronautical Congress in Sydney alongside professor John Bellardo, director of the CubeSat Lab.

Coming Full Circle

As the SAL-E team prepares for launch, the mission is once again drawing support from deep inside the Cal Poly CubeSat legacy.

Coelho, now director of programs at Maverick Space Systems, is arranging and funding SAL-E’s ride to space, a contribution valued at $150,000. For him, it’s a way to give back and continue the Learn by Doing spirit that shaped his career.

He’s one of the many alumni whose fingerprints are on the program’s foundation. Another is Jeremy Schoos (Aerospace Engineering ’01), who in 1999 kick-started CubeSats at Cal Poly, bringing co-creator Bob Twiggs to campus and recruiting a cross-disciplinary team to design a device that could safely release CubeSats into orbit.

Working with little more than whiteboards and mills, Ryan Connolly (Manufacturing Engineering ’00) and the first team transformed a fledgling idea into flight hardware — the Poly Picosatellite Orbital Deployer, or P-POD, which gave the satellites a reliable way to reach space.

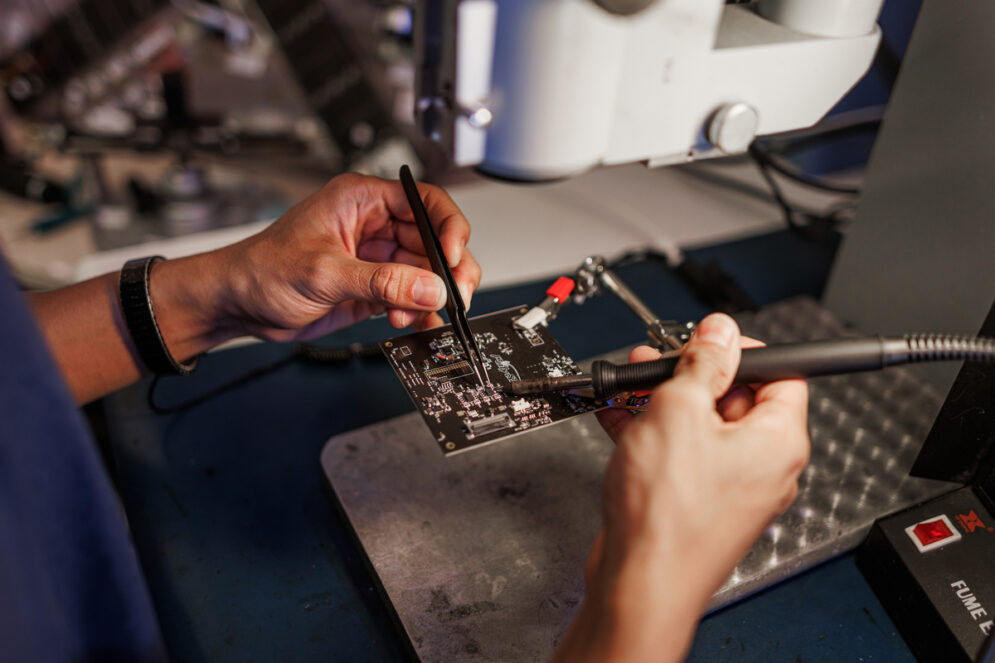

CubeSat team member Berfredd Quezon solders a circuit board that will help guide a student-built satellite through space.

When Schoos graduated, Jake Schaffner (Electrical Engineering ’04), who had first attended meetings while at Cuesta College, took over. He helped formalize systems that became standard practice, but earning a spot on a rocket was still an uphill climb.

“We were going to conferences and visiting aerospace companies across the country, presenting to anyone who would listen,” said Schaffner, who served as CP1 mission lead. “It was tough to be taken seriously or make progress on an affordable U.S. launch option.”

Despite the doubts, the team kept pushing.

Each launch built trust and propelled the work forward, as partners signed on and alumni moved into the industry. In time, the program carved out its place in the space community.

“You don’t have to wait until you graduate to do meaningful engineering. That’s what this lab proves — students can do incredible things when they’re trusted with the responsibility.”

PROFESSOR JOHN BELLARDO, CUBESAT LAB DIRECTOR

Over the past two decades, Cal Poly CubeSat alumni have shaped missions at NASA, SpaceX, JPL, Northrop Grumman and a constellation of startups. Some helped develop the first iPhones, applying their skills with compact radios and sensors. Others contributed to satellite networks like Starlink, scaling CubeSat principles to global infrastructure.

Every spring, many return for the CubeSat Developers Workshop, a Cal Poly–hosted conference that draws hundreds of engineers, researchers and students from around the world. Today, the lab is a hub for innovation, collaboration and community in the aerospace industry.

“Looking back, it’s amazing how far it’s come,” Schoos said. “But the foundation was always there: students doing real engineering, even when few believed something that small could work.”

Passing the Torch

Cole Fehring still remembers the silence after the explosion.

It was September 2021, and he was watching from his dorm room in yakʔitʸutʸu as Firefly Aerospace attempted its first launch, carrying Spinnaker 3, the mission he’d helped lead as a student in the CubeSat Lab.

The rocket rose into the sky but then veered off course and disintegrated in a midair fireball, visible across San Luis Obispo as a streak of smoke hung in the air.

“I saw it blow up from my window before they even announced it on the livestream,” said Fehring (Aerospace Engineering ’23). “It wasn’t totally unexpected since it was a new company’s first launch, but it still hit hard.”

At the time, the lab was still recovering from the pandemic. Membership had dropped. Projects had stalled. Fehring stayed on through it all, helping rebuild the team from the ground up.

That fall, Bleakley and Thompson were among the freshmen Fehring drove to see their first rocket launch — a Delta liftoff viewed from Ocean Avenue in Lompoc, camp stove and inflatable couch in tow. Later, both helped carry the tradition forward, bringing new students on launch trips of their own.

Now the lab is full again and hitting its stride.

First photo: Electrical engineer Francine Canal (right) works with her mentor Ethan Spalard while testing circuit boards in the CubeSat Lab. Second photo: The CubeSat’s counterweight, engraved with the names of students who worked on the project.

Ethan Spalard, a graduate student in electrical engineering, first joined as an undergrad and quickly became a driving force on SAL-E. He led the avionics team through high-stakes test cycles, serving as the responsible engineer for the payload interface board, the link between SAL-E’s hardware and its scientific instruments.

When Spalard left for a summer internship, the lab needed someone to take over a critical role. Francine Canal, an electrical engineering student and recent transfer to Cal Poly, stepped up. Just a year earlier, she’d joined the lab as Spalard’s mentee, new to campus, new to the project and eager to learn.

Under his mentorship, she’d learned the tools and protocols of the job. Now she was the one keeping SAL-E’s avionics work on track, managing test procedures and navigating tight deadlines with the help of teammates who had once guided her.

“It was a full-circle moment,” Spalard said. “That’s what this lab is built on: people helping each other grow into the job.”

Bellardo has spent years helping students take on ambitious missions while building the structure that allows them to lead.

“You don’t have to wait until you graduate to do meaningful engineering,” he said. “That’s what this lab proves — students can do incredible things when they’re trusted with the responsibility.”

First photo: Computer engineer Akshay Sathish (left), aerospace engineer Kayla Wong (center) and aerospace engineer Drew Stannard-Stockton (right) work with the Friis ground station, used for talking to CubeSats in orbit, on the roof of the Engineering IV building. Second photo: Mathematics student Lizzy Gross (left) and Sathish adjust the antenna.

That cycle of learning, leading and lifting up the next generation defines the CubeSat Lab as much as any launch. New members are paired with mentors to carry forward technical knowledge and team culture. Students come in with curiosity and leave with hard-won experience, forged through the challenge of designing real hardware for space.

Aerospace engineering student Sage Russell has helped shape that experience for many. While supporting mechanical systems on SAL-E, she also leads education and outreach for the lab, giving classroom talks, welcoming new recruits and helping students across campus imagine their own futures in space.

“We build CubeSats,” she likes to tell them. “Tiny cube-shaped satellites — it’s exactly what it sounds like.”

The simplicity of that statement belies the complexity of the work and the weight of its impact. In just over two decades, the program has grown into one with global reach, powered by the CubeSat standard developed at Cal Poly, a model that has helped more than 200 satellites reach orbit and enabled five countries to become spacefaring nations.

But the program’s most enduring legacy may be the people it has shaped.

Students from the lab have gone on to lead missions, design spacecraft and build companies, not just because they learned how to solder a board or write flight software, but because they learned to take ownership, collaborate under pressure and believe their ideas belonged in orbit.

Today, as the next generation prepares to take the reins, that momentum continues. SAL-E and AMDROHP will soon be in space. Others will follow. And the lab will keep reaching higher, launching missions — and the careers of the students who make them possible.

Payloads with a Purpose

SAL‑E will carry two student-designed payloads that test emerging technologies in orbit.

SAL‑E will carry two student-designed payloads that test emerging technologies in orbit.

SQUAD: SPACE QUACKER ADVANCED DEVELOPMENT

SQUAD grew out of a Cal Poly senior capstone that connected students with OWL Integrations, a tech company focused on resilient communications. The payload will test a long-range radio device in the harsh environment of space, collecting data on its performance in orbit.

“We wanted to push our hardware further and validate it in space,” said Kevin Nottberg, a computer engineering graduate and current electrical engineering master’s student who led the hardware and firmware development. “Getting this project off the ground has been a dream come true.”

CARP: COMPUTER ARCHITECTURE RESEARCH PROJECT

Designed by Cal Poly students using open-source silicon and custom firmware, the CARP chip will be monitored for how it responds to radiation and other environmental stressors in low Earth orbit.

“We’re interested in how this chip’s silicon reacts to radiation in orbit,” said computer science major Miguel Villa Floran. “It’s a unique opportunity to study real-world effects on open-source hardware.”

Your Next Read

A timeline of Cal Poly’s role in humankind’s journey to reach for the stars, from alumni astronauts to student-built satellites.

Architecture alumnus BenjaminTom helps shape the spaces at Jet Propulsion Laboratory so engineers and scientists can do their best work.