Cal Poly's Astronauts

Robert “Hoot” Gibson

From a childhood in the skies to orbital space flight, Cal Poly’s first alumni astronaut used Learn by Doing to carry him ever higher.

By Larry Peña // Illustration by Kyleigh Pinto

Share this article:

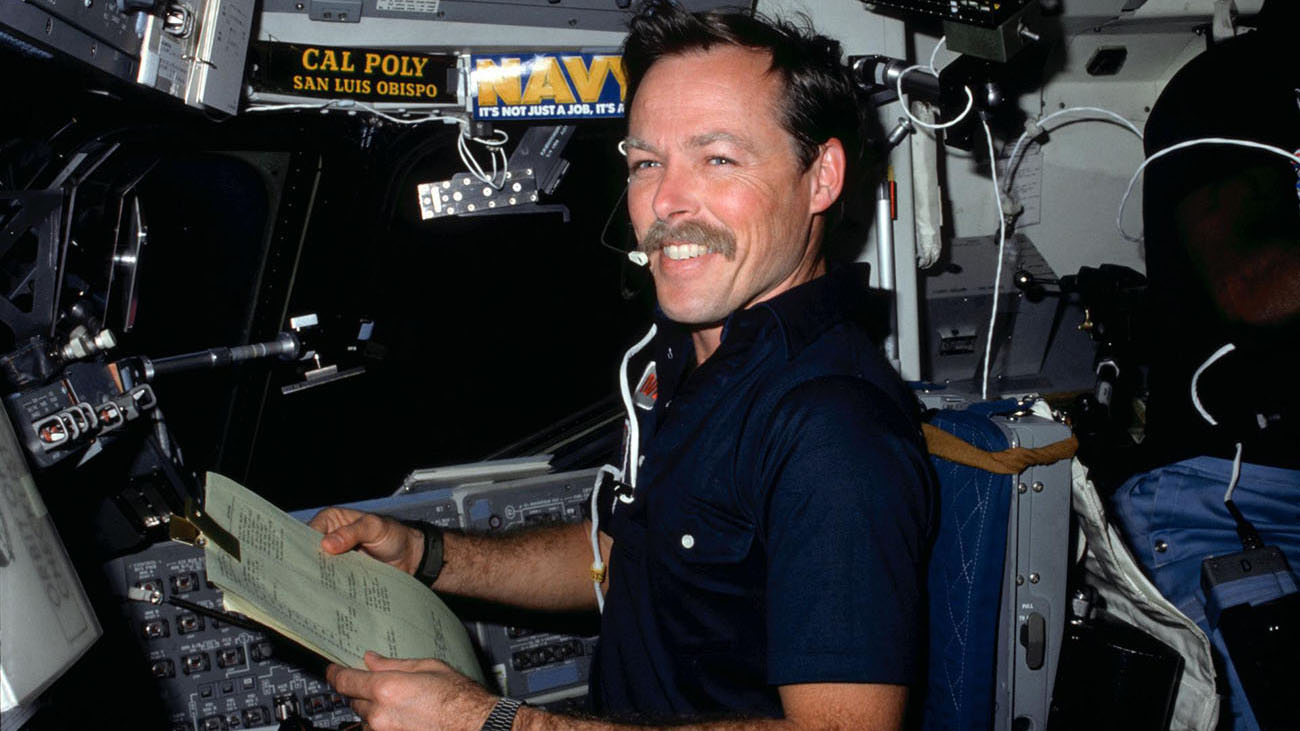

Gibson on the flight deck of the space shuttle Challenger during his first orbital mission in 1984. Photo courtesy of NASA.

Robert Gibson was born to fly — but he never particularly wanted to be an astronaut.

“I was an airplane person, and astronauts just flew capsules,” he says. “Capsules don’t have wings on them. I didn’t want to be, as Chuck Yeager once said, ‘Spam in a can.’”

All that changed when a group of astronauts visited the Naval Air Station in Miramar, California, where Gibson, a Naval fighter pilot, was assigned to a squadron flying the brand-new F-14 Tomcat. The astronauts told him about a new NASA program to develop a new airplane-inspired orbiter: the space shuttle.

“From that moment on, I said, ‘I have got to get me one of those,’” says Gibson, who in 1984 became the first Cal Poly alumnus to travel into space.

ROBERT “HOOT” GIBSON

AT A GLANCE

CAL POLY MAJOR

Aeronautical Engineering, 1980

NAVY CAPTAIN AND FORMER FIGHTER PILOT

5 SPACE MISSIONS

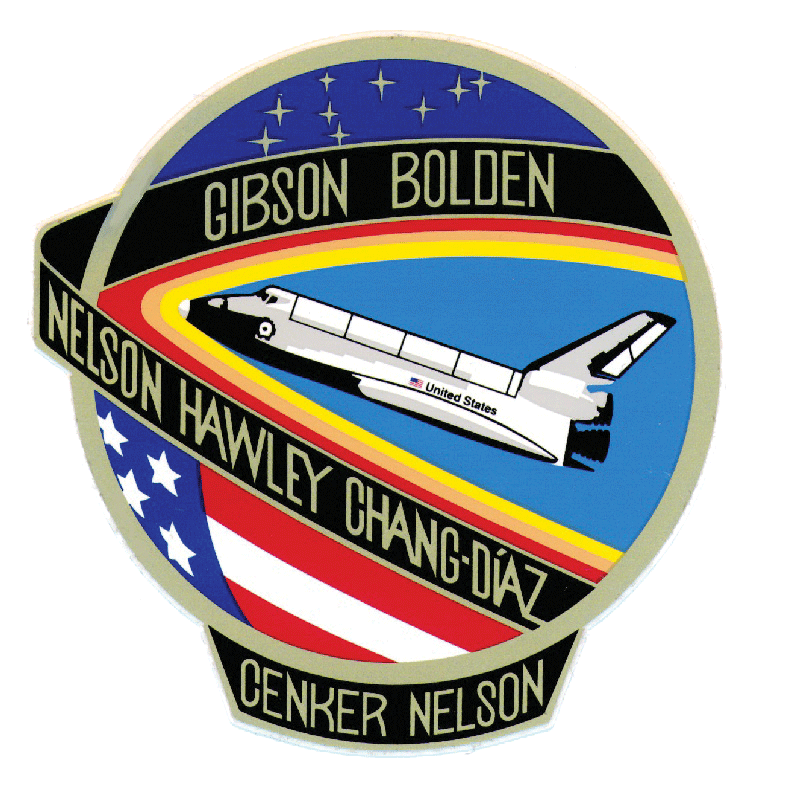

1984 - Piloted space shuttle Challenger on an eight-day orbital mission that included the first untethered spacewalk

1986 - Piloted space shuttle Columbia on a six-day mission to deploy communications satellite

1988 - Four-day mission aboard space shuttle Atlantis — his first as mission commander

1992 - Eight day mission aboard space shuttle Endeavour to conduct microgravity research with Japan

1995 - Nine-day mission aboard Atlantis, first American mission to dock with Russian Mir Space Station

TOTAL TIME IN SPACE

36 DAYS

4 HOURS 15 MINUTES

SERVED AS CHIEF OF THE ASTRONAUT OFFICE

His journey to the skies — and beyond — began before he was even born. His parents met when his mother celebrated graduating from teaching college by taking flight lessons from his father, a pilot and flight instructor.

When Gibson was 10, his father became an aeronautical engineer and professional test pilot. From that moment, Gibson wanted nothing more than to follow in those footsteps. He took his first flying lessons from his dad as a young child.

When choosing colleges, it was Cal Poly’s aeronautical engineering program and campus hangar and runway — combined with California weather, nearby surf and an affordable price tag — that sealed the deal for him.

After transferring from a community college in New York, Gibson began loading up on credits right away. He loved that the program gave such a comprehensive look at the engineering process, from theory and conceptual design to welding and fabricating those designs by hand.

“Cal Poly was determined to produce engineers that know how to design things, not engineers that would design something that was impossible to make,” Gibson says.

He had another motivating factor: With the Vietnam War in full swing, he was on a tight deadline to finish his degree or get drafted and ship out. He was able to defer just long enough to graduate, and with his civilian pilot’s license, he was able to join the Navy’s pilot training program in Pensacola, Florida.

He trained on a series of ever more powerful planes. The Beechcraft T34 was similar to a civilian plane his dad had trained him on. The T2 Buckeye was his first single-engine jet, and its acceleration shocked him. His first combat plane was the A4 Skyhawk, and he eventually piloted the F4 Phantom, his first experience going beyond the speed of sound.

Gibson excelled as an engineering student, as a fighter pilot and as a test pilot. But once he was accepted into NASA’s astronaut candidate program in 1978, he was shocked to find himself back at the bottom of the ladder.

“You could put me in any jet fighter, and if I knew how to start it, I could fly it,” he said. “This was entirely different. I’d never flown in space. So there was a low point that I experienced when I got to NASA because I felt really dumb.”

Gibson spent four years working behind the scenes on engineering projects, testing systems and assisting with mission preparations. He was just thinking about asking for a higher-profile role, when the chief astronaut asked if he would consider piloting an upcoming mission.

“I thought, ‘Holy smokes,’” he says. “Here’s something I’ve been waiting for for four years, and all of a sudden it was here, and I wasn’t ready for it.”

Gibson put in another year of focused training to reach his goal: launch day as pilot of the shuttle Challenger in February of 1984. He remembers passing Mach 3 during the launch, the fastest he had ever traveled.

“All my jet fighters paled in comparison,” he says. “The engine shut down, and I got this smile on my face that was about this big across, and I said, ‘Wow, that was fun. I wanna go back and do that all over again.’”

Not all shuttle missions went so smoothly. Just 10 days after he returned to Earth from his second mission, in 1986, NASA’s next mission met with disaster when Challenger exploded moments after launch. Gibson was assigned by the Kennedy Space Center to help investigate what went wrong with the rocket assembly and advise the redesign to prevent similar failures.

“We went through everything from top to bottom after the Challenger accident, and of course, the engineering was a big help because of the structural issues we had to look at,” he said. “So once again, because of Cal Poly and things that they taught me, it was something I was well prepared for.”

That experience was still on Gibson’s mind during his own close call on his third mission in 1988. Shortly after launch, he noticed hundreds of damaged heat shielding tiles on the right wing of the craft.

“Iʼll never forget when we brought the image up on our onboard TV,” he said. “I said to myself, ‘We are gonna die.’”

On the ground, the NASA mission control team disagreed with Gibson’s assessment. The crew completed their mission in good spirits, but during the final descent Gibson was on high alert, watching for that right wing to take critical damage that could doom the ship and crew.

Fortunately, the tiles held together and the crew landed safely, and the post-mission analysis registered only a close call and not a disaster.

“All my jet fighters paled in comparison. The engine shut down, and I got this smile on my face that was about this big across, and I said, ‘Wow, that was fun. I wanna go back and do that all over again.’”

Robert "Hoot" Gibson

First photo: The crew of space shuttle mission STS-47. Gibson (back row right), the mission commander, with crewmates (back row, left to right) Jerome Apt, Curtis Brown, (front row, left to right) Jan Davis, Mark Lee, Mamoru Mohri and Mae Jemison. Second photo: A now-iconic image taken by Gibson during his first shuttle mission, featuring crewmate Bruce McCandless running the first field test of the manned maneuvering unit. Photos courtesy of NASA.

Gibson’s fifth mission in 1995 was a historic moment for international cooperation when he was assigned to command the first U.S. mission to dock with Russia’s Mir Space Station and collaborate in space with a Russian crew. It was early days after the end of the Cold War, and the mission was a key test of the two nations’ ability to overcome still-simmering tensions and collaborate on a project for all humanity.

Technologically, diplomatically, organizationally and even linguistically, it was one of the biggest challenges NASA had ever faced. It was years before the International Space Station, and the shuttle had never docked with anything before. The crew spent weeks training in Russia with their cosmonaut counterparts to learn Russian, get a feel for the technology and figure out how to integrate two vastly different systems.

“That was the most exciting mission that I got to fly,” he says. “Given the degree of difficulty, it just came off virtually flawlessly. It was a real tribute to our training and to this really great crew that we had put together.”

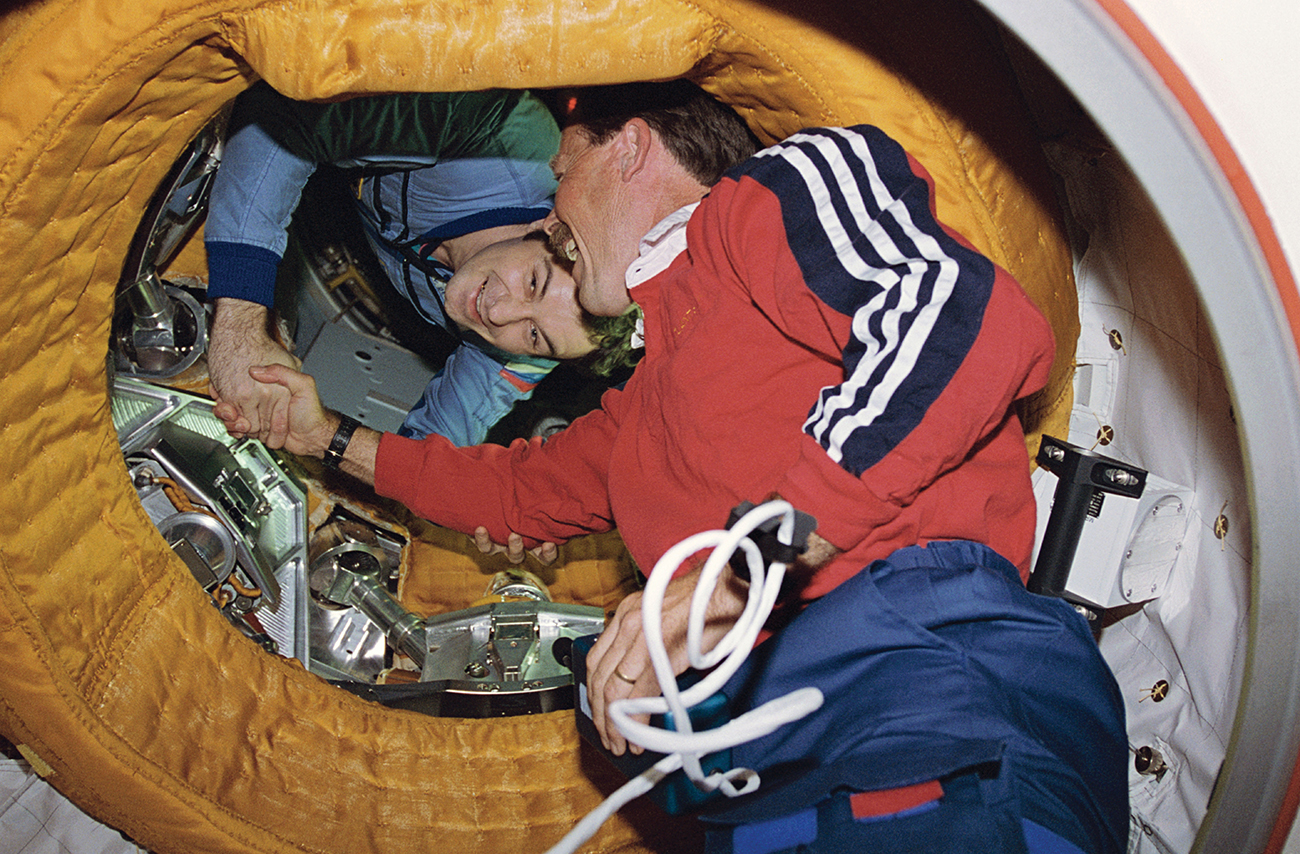

Gibson, right, shakes hands with Russian cosmonaut and Mir commander Vladimir Dezhurov in a historic moment of international cooperation. Photo courtesy of NASA.

Besides that historic mission, Gibson is most proud of the time he served as NASA’s chief astronaut. The role made Gibson head of the astronaut corps, top advisor to the NASA administrator on astronaut training and operations, a key voice in selecting new candidates, and a lead planner of the corps’ activities and flight crew assignments.

Gibson has continued to pay close attention to NASA’s efforts since retiring in 1996 and sees both threats and opportunities in the current trajectory of space travel.

“The innovation that the private industry is bringing to us — Blue Origin, SpaceX, Virgin Galactic — I see those as all very, very good things,” he says. “I hope we don’t lose our way with all these gigantic budget cuts that our present president is putting on us. NASAʼs never going to have enough money, especially now, to do it all themselves.”

From a passion for the skies to his many journeys beyond them, Gibson traces one constant that he’s used every step of the way.

“I was practicing learning by doing learning how to fly with my dad, and what I learned at Cal Poly got me started on my road as an astronaut not knowing anything,” he says. “Learn by Doing made it all possible.”

Your Next Read

From road racing at Cal Poly to private space flight, one Mustang astronaut has spent four decades as the ultimate team player.

Nestled in between the arms of Building 52, the Cal Poly Observatory is both a portal to the stars and a tool for meaningful research.