Cohousing the Unhoused

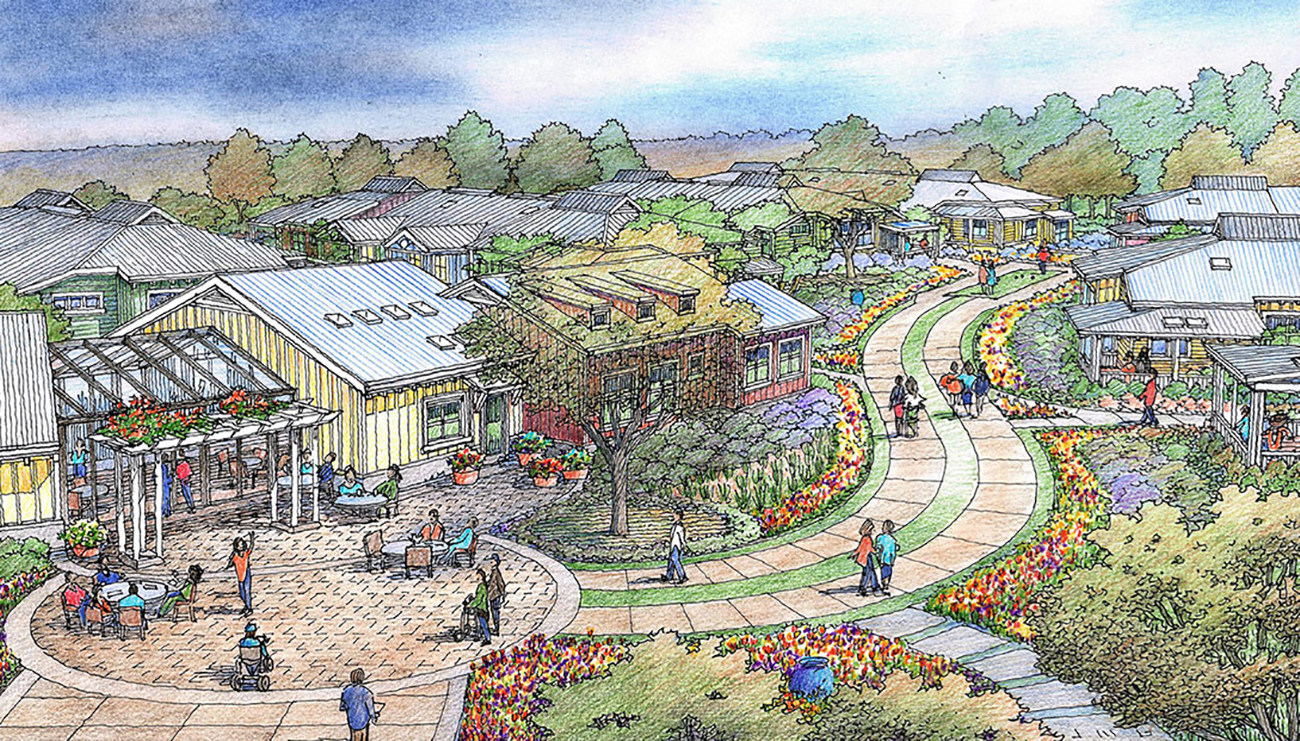

Charles Durrett wants to apply a very traditional model of community to the modern challenge of homelessness.

A pivotal moment in his Cal Poly education transformed Charles Durrett (Architecture ’82), leading him to embrace a housing model that is both innovative and incredibly traditional. Now, Durrett wants to bring that model back to San Luis Obispo as a potential solution for homelessness in the county.

Durrett is the founder of The Cohousing Company, an architectural design consulting firm that specializes in developing intentional communities of private homes clustered around a shared space, where residents work together to collectively manage a shared pool of resources.

Since launching the Cohousing Company, Durrett has helped develop more than 50 such communities across the U.S. and Canada — including his family’s own home community in Nevada City, California.

“The whole thing is set up to acknowledge cooperation as a vehicle for making the world better for you as an individual,” Durrett said. “It turns out that a great deal of our individual interests are better served by making some decisions collectively.”

Charles Durrett

Durrett discovered the concept during his fourth-year architecture study abroad experience in Copenhagen, Denmark, where the idea was developed in the 1960s. After graduation, he returned to Copenhagen to learn more about the concept and introduced cohousing to the U.S. in 1988 with his book “Cohousing: A Contemporary Approach to Housing Ourselves.”

He says that the benefits of the cohousing concept are too many to list, but perhaps the most important include affordability and sustainability. While each family in a cohousing community owns their own private residence, many resources are shared: recreational equipment and communal areas, yard equipment, sometimes even vehicles. The homes are designed to be smaller than the average American home and more energy efficient.

But for Durrett, the biggest benefit of the cohousing model is psychological.

“Kids growing up in these communities gain so much practical exposure and experience with being so connected to other families,” he said. “You can’t beat what it does for seniors — about 40% of whom are pathologically lonely. Cohousing addresses that and about a hundred other emotional well-being topics. The ability to walk home and say hello to 20 neighbors along the way — it’s not the beginning and the end, but it’s a big part of healthful living.”

The mental and emotional impact, Durrett says, is a huge part of what he thinks would make cohousing a particularly effective cure for homelessness in San Luis Obispo County, which has risen by 32% in recent years.

“These people have been so cast aside and judged that they have serious self-confidence issues,” he said. “Building the cottage is one thing, but co-managing the neighborhood gives them more confidence than anything else. They learn how to deal with other people. And once they get that confidence together, they can move mountains.”

Durrett acknowledges the evidence that suggests providing a home is the effective and cost-efficient way for a community to address homelessness — but he says cohousing takes that idea a step further.

“I believe in a ‘housing first’ approach,” he said. “But if you put a community together, you can make housing, and then so many other positive and healthy things can happen via that cooperation. So I’m a big believer in ‘community first.’”

At a recent San Luis Obispo community workshop called “A Solution to Homelessness in Your Town,” Durrett presented the concept as a way to alleviate the crisis of homelessness in the area. About 250 people attended the event in person and online, including several county policymakers.

If you put a community together, you can make housing, and then so many other positive and healthy things can happen via that cooperation.

“This is a significant moment when all of us — elected officials, homebuilders and residents — join to address the shifts in our demographic, socioeconomic and environmental situations,” said County Supervisor Dawn Ortiz-Legg. “Mr. Durrett has brought forth a concept that is historically a village — all ages, mixed in and living together to support each other. This type of housing is what I want to create, with housing complexes that are multigenerational, where people can have a variety of housing types to fit their specific life chapter needs.”

Implementing such a plan to address homelessness in the county will be an uphill climb. But in the meantime, Durrett hopes budding architects at Cal Poly can help play an impactful role in addressing homelessness, as well as the larger challenge of affordable housing generally in San Luis Obispo County — and he would love to work with students who are interested in getting involved.

“I think there’s a great opportunity for architecture students at Cal Poly to get involved with creating homeless projects in SLO,” he said.

For Durrett, cohousing is part business, part passion project, part humanitarian effort. He recently spent time in eastern Poland applying the cohousing model to help develop childcare centers and housing facilities for refugees fleeing the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

“From the beginning, our office has done what we thought we had to do because it was the smarter thing and the better thing to do,” he said. “I’m not only an architect. I have to approach architecture from a very anthropological and activist point of view.”

Want to see more stories like this in print? Subscribe now to receive a free copy of Cal Poly Magazine twice a year.