Alumni Profile

The Legacy of

Walter Harris

One groundbreaking alumnus was recently honored for his work helping to extend opportunities to generations of Cal Poly students.

By Larry Peña

Share this article:

Walter Harris at the Cal Poly Administration Building, where he worked for decades as a key member of the admissions and recruitment team. Photo by Joe Johnston.

At a campus ceremony in January, the Office of Student Diversity and Belonging presented alumnus and longtime Cal Poly administrator Walter Harris (Sociology ’73) with the MLK Legacy Award for his work advancing equality, opportunity and justice in the campus community.

“This award recognizes someone who epitomizes progress toward making Cal Poly a better place for African American students,” said Jamie Patton, associate vice president for student affairs, diversity and inclusion. “With Mr. Harris, it goes beyond students. The impact that he had expands to faculty and staff, and it expands even to the community.”

Born in Arkansas and raised in Fresno, Harris was introduced to Cal Poly by his high school guidance counselor, who encouraged him to apply. When he arrived on campus in 1968, he was one of just 48 Black students out of 10,000.

Harris and the other 47 students quickly learned to lean on each other for social connection.

“It was a whole different world coming from the west side of Fresno,” he said. “Fortunately, we had current students here who took the new students under their wings and mentored us.”

Harris was one of the first students to participate in the Educational Opportunity Program (EOP). This statewide effort was meant to provide support for CSU-qualified low-income students whose parents did not have a college education.

Cal Poly ran a pilot version of the initiative in 1968 ahead of the program’s official launch statewide the following year. Harris was one of 22 students admitted to Cal Poly as part of that test cohort.

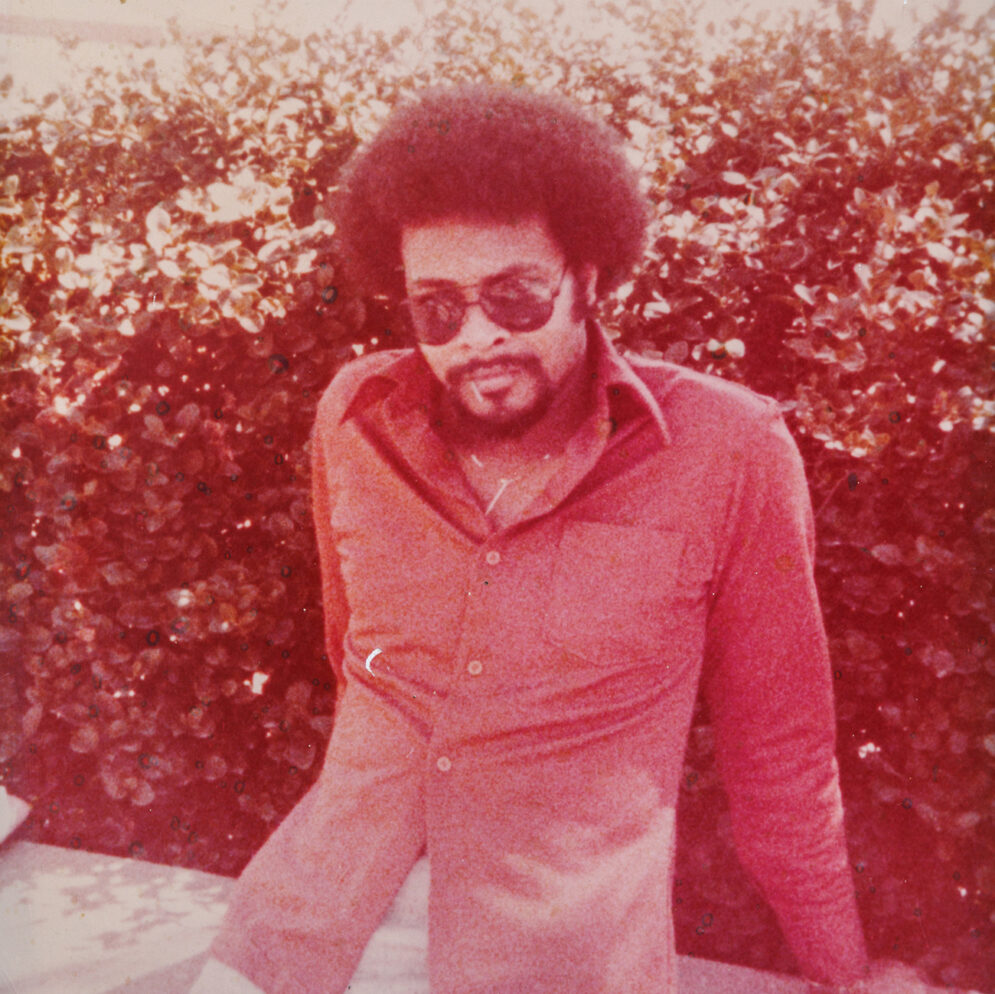

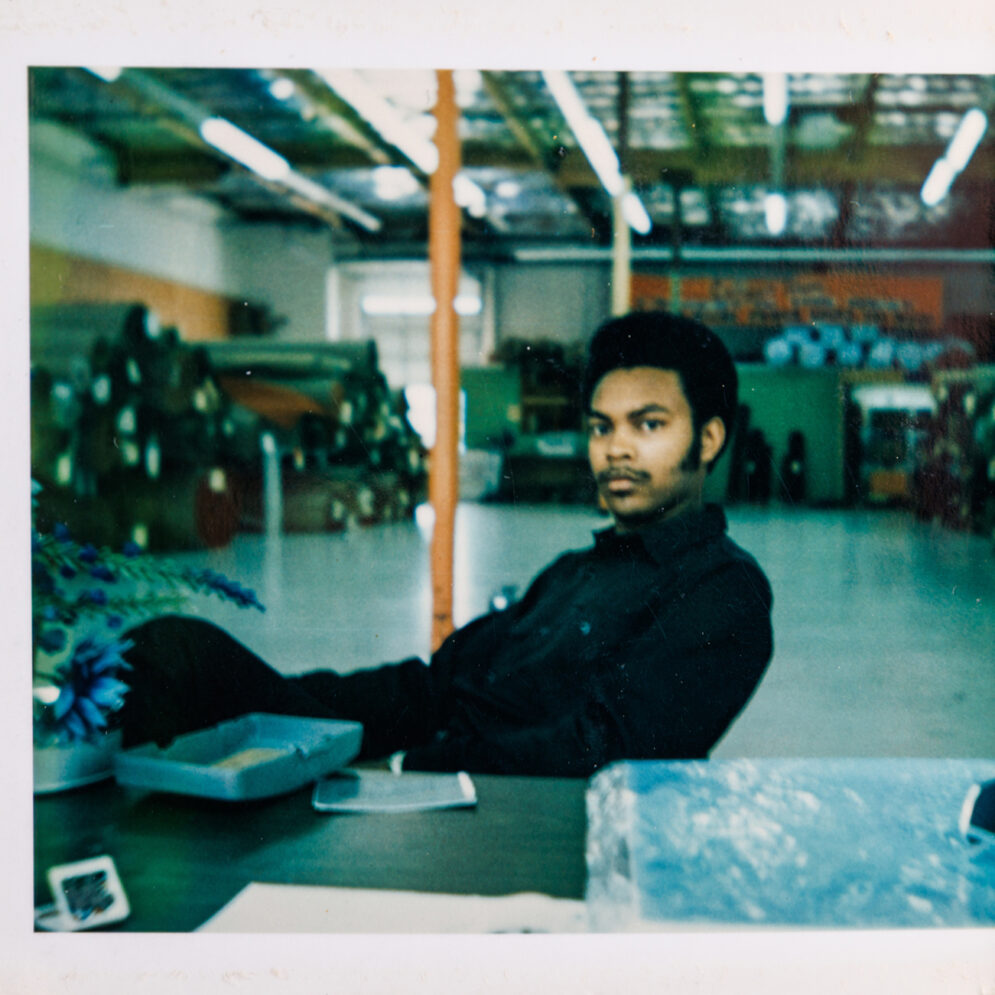

Harris as a freshman in 1968 (first photo), and shortly after graduation in 1973 (second photo).

As an EOP student, Harris attended twice-weekly meetings with the program’s counselors, who helped address barriers to academic success and social and emotional wellbeing. The program provided mentors to help the students get acclimated to the academic rigors of college life.

Originally an engineering major, Harris realized after just one quarter that engineering wasn’t the best fit for his strengths. He switched to sociology due to an initial interest in criminology and took hands-on internships with a youth correctional facility and probation officers, as well as a work-study job at the California Men’s Colony prison just up the road from Cal Poly.

“I just found that engineering wasn’t the thing that was going to allow me to do what I do best, and that’s interact with people,” he said. After graduating in 1973, Harris applied for a campus staff job to help pay the bills while he pursued a master’s degree. His first job on campus: EOP counselor.

“I have students throughout the country who have been able to say, ‘I’ve now made it — because someone reached out and was willing to provide some assistance when I needed it.'"

Walter Harris

“I knew what the students were up against because I had gone through it. I knew the challenges that they were facing. I could provide insight to help someone else overcome whatever frustrations they may have been feeling,” said Harris. “I could tell them, ‘I’ve already traveled this path, and I’ve gotten my degree. If I can, you can.’”

In the 1980s, Cal Poly President Warren Baker created the department of University Outreach Services, which merged the EOP’s separate recruitment process focusing on low-income, first-generation students with the university’s overarching recruiting efforts. Harris was instrumental in making sure EOP-eligible students didn’t get lost in the shuffle.

“Without EOP, a lot of qualified students would have never had the opportunity to get a college degree from a place like Cal Poly. They would visit this place and look around and like the environment, but then they would say, ‘Oh man, I don’t even have a chance. I shouldn’t even put in an application,’” Harris said. “But then, we’d be able to sit down and tell them, ‘Yes, you can put in an application! But here are some things that you may have to do ahead of time to get better prepared.’”

Harris didn’t leave his passion for supporting students at the office. His son, Terrance, recalls a steady stream of students coming through their family home in San Luis Obispo — meeting with Walter for counseling, getting rides to church with the Harris family, or stopping by for a home-cooked Sunday dinner. “I’m always running into people who will talk about the impact that my dad had on them, and it was that personal connection that he made with students,” said Terrance.

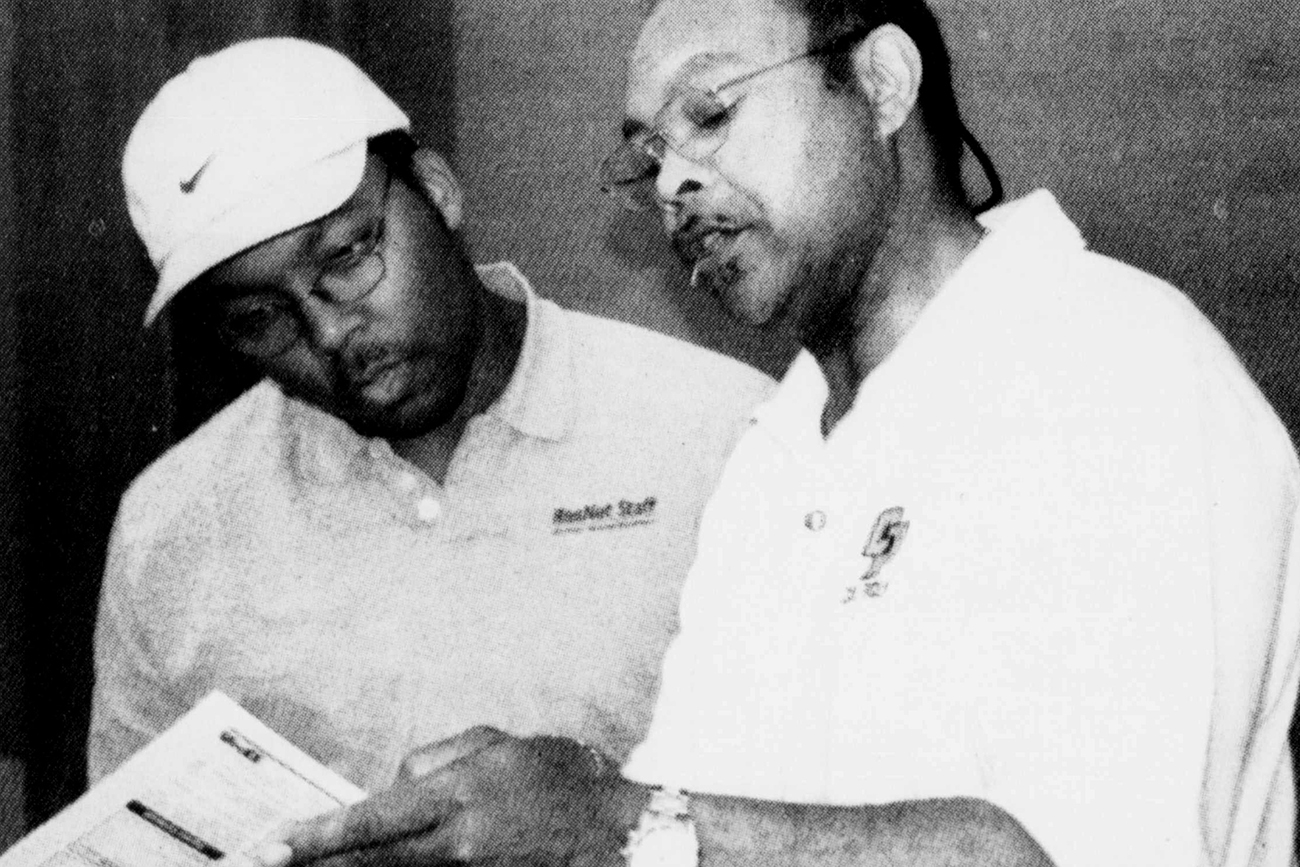

Harris (right) speaks with business student Elbert Hardeman at a 2002 forum on campus diversity. Photo by Sierra Fish, courtesy of Mustang News.

Harris retired in 2012 as associate director of admissions and recruitment, capping a 39-year career convincing promising students to commit to the Learn by Doing experience — and supporting them once they did. The initiatives he helped lead set the foundation for many of the academic support programs that still provide crucial assistance to students facing barriers to education.

“I have students throughout the country who have been able to say, ‘I’ve now made it — because someone reached out and was willing to provide some assistance when I needed it,’” he said.

Since retiring, Harris has continued to serve the Cal Poly community. He has facilitated events with the Black Faculty and Staff Association and the Black Student Union. He also often caters departmental functions across the university as a local barbecue legend.

And beyond the legacy of thriving students and a connected campus community, he has left one last significant impact: His son, Terrance, followed in his footsteps. From his start as a student assistant working with his dad in the admissions office, Terrance is now the university’s vice president for enrollment and student affairs.

“I grew an appreciation for what he did,” said Terrance. “I learned a new level of respect for his knowledge and his ability to engage a crowd, and for his ability to articulate the benefit of Cal Poly. I think I really grew to understand him a lot more working with him.”

After nearly six decades of involvement with Cal Poly, Walter Harris is proud to look around his university and recognize what has changed — and what hasn’t. “I see that there are still individuals today who care,” he said. “They want to see a campus that is more diverse. They are interested in others as well as themselves. They want to see others improve. We want to see other lives increase.

“To me, that’s what education is about. That’s what our society is supposed to be about. That’s what our community is supposed to be about.”

Your Next Read

At the Women’s Mobile Health Unit, students explore the medical field while providing free care to a vulnerable population.