More than 20 years ago, Christina Hernández was browsing her local library when she came across the book that would change her life.

It was a coffee-table book, thick with glossy full-page color photos of galaxies and planets. She flipped through the pages and landed on a photograph of Saturn. She couldn’t fathom how someone was able to get that picture.

“It started there. That was really where the seed was planted,” Hernández said.

Hernández continued to nurture her interest in space: attending a magnet high school for math and science (she was on the robotics team), studying aerospace engineering at Cal Poly, and ultimately landing a position as a payload systems engineer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

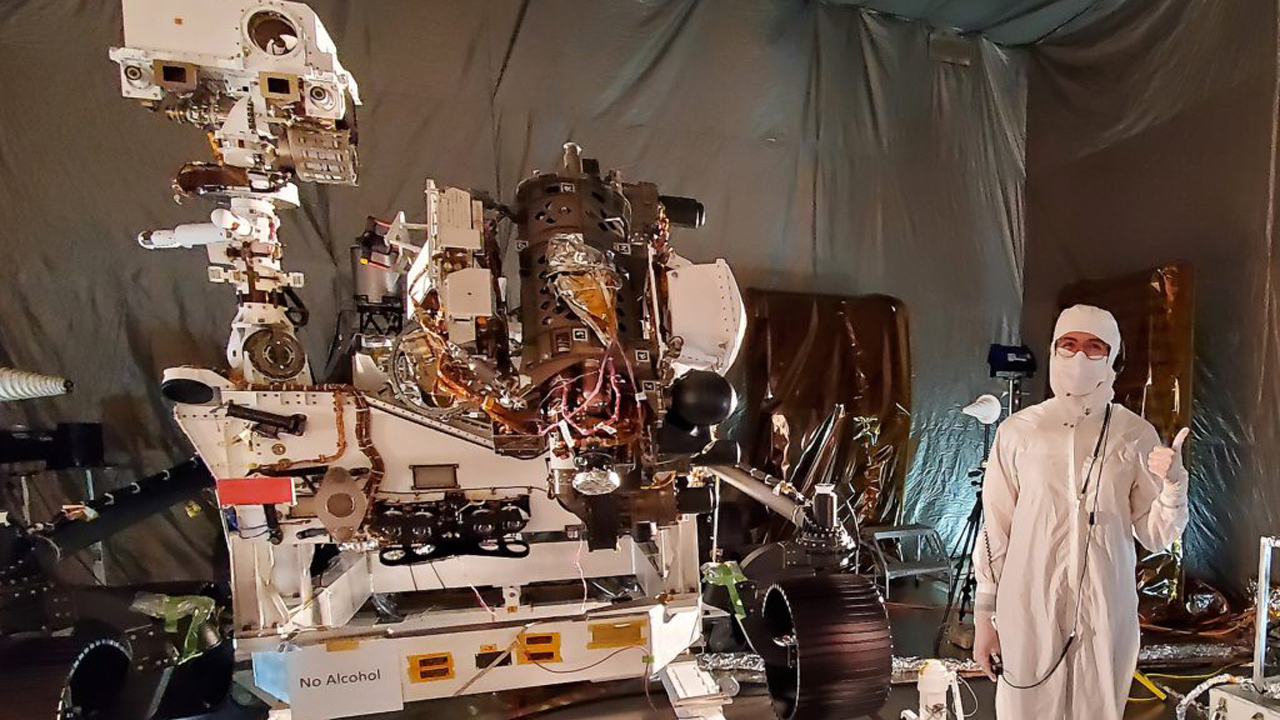

Now, instead of looking at pictures of planets, she’s helping land robots on them — she’s part of the team that landed the Perseverance rover on Mars in February and continues to “talk” to the rover and collect data from it while it explores the Red Planet.

“I’ve had the opportunity to see the rover from a very preliminary design all the way through seeing these instruments turn on for the first time from Mars,” Hernández said. “That’s really surreal, to see that breadth of an engineering project.”

But it wasn’t a smooth road. The kid who was so passionate about learning encountered fear, discouragement and insecurity on her journey to NASA: feelings she was able to combat as she found likeminded peers, support networks and mentors. Now, Hernández hopes to pay it forward as she encourages the next generation of women and other underrepresented groups in STEM.

A Lifelong Learner

Growing up in Los Angeles, Hernández wasn’t one to tinker around. She did her learning and exploring through reading, bolstered by regular trips to the library with her mom.

“Eventually you ask yourself, ‘How do I get there?’” she said, adding that it gave her a “lifetime learner” mindset. “With that mentality, you naturally start to pick up math and science.”

That passion for learning has impacted the people around her. Her mom still remembers the names of all the clouds thanks to one afternoon after third grade, when an excited Hernández pointed out every cloud in the sky.

“I just wanted to know everything and show off all the things I learned in school that day,” she said. “My parents were always supportive of me asking annoying questions and being that know-it-all kid.”

Hernández followed her passion for aerospace to the California Academy of Math and Science, where she participated in the FIRST robotics team and first heard about Cal Poly from some of the school counselors.

‘Don’t be afraid to raise your hand’

Though Hernández came to Cal Poly prepared by a rigorous high school curriculum and an internship with aerospace and defense technology company Northrop Grumman, she struggled. The academic challenges of the fast-paced quarter system and the aerospace engineering program were compounded by her lack of a support system and awareness of being the only woman or woman of color in many of her classes.

“The quarter system is so fast-paced and the AERO program is brutal. That is a tough engineering environment,” she said. “When I got in, I was like, ‘Whoa, I’m not the best anymore. I don’t relate to anyone. How do I study, how do I learn, how do I navigate this?’

“Early on in my years at Cal Poly, I didn’t have the same support system as my peers who grew up steeped in aerospace engineering culture, so it kind of felt like I was navigating this on my own,” she continued.

It wasn’t until her propulsions class, taught by Tina Jameson, when things started to click into place. The class was firing jet engines, and Jameson asked who wanted to turn the engine on, Hernández remembered.

“The normal ‘AERO geek’ gut reaction is to raise your hand, and she noticed that I hesitated,” Hernández said. “She let another student turn it on and then she came by me and whispered, ‘Hey, don’t ever let fear hold you back. You know how to do this; I will help you along the way. Don’t be afraid to raise your hand.’”

The comment stuck with Hernández. She was struck that another woman, an aerospace engineer, noticed that she had been hiding even though she was capable.

“The next time she asked, of course I raised my hand,” Hernández said. “That meant the whole world.”

Soon, Hernández found her confidence — as well as peers in the Aerospace Engineering program, relationships with professors like Jameson and Kira Abercromby, and the Multicultural Engineering Program, where she currently serves on the industry advisory board.

“The MEP was one of those safe havens that really helped make me feel like ‘Hey, we’ve got your back if you’re struggling, if you need tutoring, if you need mentoring, if you need help getting an internship — it doesn’t matter. We’re here and it’s OK to ask for help.’”

Finding that community shifted Hernández’s mentality.

“I started doing better in my classes. I started feeling like I was an aerospace engineering major and I started to feel like I was a top performer,” she said.

‘There’s space for many’

The community and education Hernández found at Cal Poly was integral to her development as an aerospace engineer, and it served her well when she landed at JPL following graduate school.

“We grow up in the student environment where it is often very centered on ourselves — we have to get the A, we have to do well — and at Cal Poly you start to do group projects and now you’re playing into the team dynamics,” Hernández said. “You understand when somebody’s having a bad day, or when somebody’s strongest subject isn’t what they’ve been assigned. This has lessons that carry all the way over into industry.”

The most important challenge, Hernández said, is learning to become an inclusive, supportive leader.

“We always talk about the technical challenge because that’s why we became engineers — those are the fun challenges. The biggest challenge is how to become a technical leader that’s still inclusive and knows how to support the team.”

And at this point in her career, that’s what Hernández is looking to become by mentoring and lifting up others.

“In my first years at JPL, it was ‘How do I get there? How do I climb? How do I become that technical person? How do I grow?’” she said. “Even though I’m not done growing technically, I still have the capability of looking behind me and helping others get to where I’m at. Especially being a woman of color, it sometimes feels like, systemically, there’s only space for one but that’s not the truth; there’s space for many.”

In addition to her own struggles, Hernández looks at the people around her who had their dreams crushed by reality — but who could’ve gone far if someone had taken the time to nurture their curiosity and understand their obstacles and barriers.

“I’ve done outreach over the years where I’ve had little kids tell me, ‘I’m really struggling at home and you saying I could work at NASA is life-changing,’” she said. “We have to acknowledge there are people who are struggling with obstacles beyond our own experience and measure. They need to be included, given a seat at the table, and lifted up. Given my privileges now, I have the opportunity to help them grow.”

And lifting people up helps everyone in the long run.

“I truly believe that math and science is in everybody. It’s natural curiosity and creativity and if you don’t grow it and nurture it over time, it tends to get trampled on by real life and its many barriers. If you can go in and lift people up, you might be able to help the next person who’s going to step foot on Mars or design the first interstellar mission. It’s that powerful.”