Space: the final frontier. It’s not just a TV tagline — it’s a pretty accurate description of the Wild West scenario taking place just beyond our skies, where rules are ambiguous at best and just about anything goes — if you can get there first.

In 2022, Cal Poly philosophy professor Patrick Lin was appointed to the National Space Council Users’ Advisory Group, a civilian group of leaders in related industries that advises the National Space Council on issues related to space policy.

Lin’s special area of expertise — the ethics of emerging technologies — puts him at the center of discussions about how we govern that final frontier as the private race for space heats up and the politics of space policy become more complex. Cal Poly Magazine sat down with Lin to ask him about some of the issues he deals with in his role as the advisory group’s resident ethicist.

Patrick Lin is a professor of philosophy

and the director of Cal Polyʼs Ethics + Emerging Sciences Group.

Cal Poly Magazine: Who, if anybody, actually governs what happens in space?

Patrick Lin: That is the million-dollar question. Even though there is some law in space, there’s not much of it. It’s very vague, and it’s not really enforceable. It relies entirely on voluntary, good-faith cooperation.

The main space laws are old — they’re all from the ‘60s and ‘70s. They’re from when only two or three nations were even space powers, and there wasn’t a lot up there. These treaties don’t talk about space debris. They don’t talk about cyberattacks.

The United Nations oversees the 1967 Outer Space Treaty (OST) and other agreements. But the thing is, the U.N. is not a world government. We all play in the United Nations voluntarily. There is no one above the U.S. that we have to answer to — same with Russia and China. If someone wanted to violate space law, there’s not really much we can do about it.

Our space laws also don’t talk much about private actors or commercial actors, so companies think they can go up there and do whatever they want.

There are companies sending human ashes up to the moon to the great objections of, say, the Navajo Nation and other groups who see the moon as sacred. There are marketing stunts — a sports powder drink that wanted to put their product on the moon so that future astronauts could use lunar ice to make a sports drink. Apparently there’s a guy who wants to build a two-story Christian cross on the moon.

There’s nothing regulating any of this. There’s no real authority in space, but at least we’ve been guided by self-interest. We know that if we go up there and started shooting satellites down, that sets a dangerous precedent. Other countries can do that to us. We’ve got the most to lose because we have the most space assets up there. Russia and China seem to be restraining themselves in the same way.

But Russia is a wild card. They have said many times that if there were a war against Russia and they were losing, they wouldn’t be afraid to nuke the world. They have also said they would take a cyberattack on one of their satellites as an act of war, which signals how vital space systems are to modern militaries. If push comes to shove and they feel that their last resort is to blow up our satellites, that could happen. It would be a dangerous precedent — their satellites would immediately be toast, the orbits around Earth would be poisoned for hundreds or thousands of years from the resulting fallout of space debris, and everyone’s space ambitions would be totally screwed.

What keeps you up at night more — a country making a harmful decision in space, or a private entity like a company making harmful decisions in space?

Both. One of them is specifically Russia doing something that would violate OST. Recently, Russia apparently planned to send up something nuclear in outer space. What it was is unclear, but it caused a lot of concern because OST forbids nuclear weapons in space. If Russia were to send a nuclear weapon, then all bets are off. Basically, they would have exited the treaty. Another scenario is that it might be a nuclear weapon not intended for targets on Earth, but to disable satellites with an electromagnetic pulse. Or there’s a possibility that maybe Russia is not sending up a nuclear weapon, but a nuclear-powered spacecraft, which is okay. We just don’t know because there’s no transparency with what other countries are sending up.

The other thing I’m worried about is these gaps in space law that open the door to businesses doing dumb things in outer space. I tend to think that we need to set down some guardrails on how we enter space. If we rush in there like anything goes, then that’s going to be very hard to undo. Other players will see this and follow.

If we rush in there like anything goes, then that’s going to be very hard to undo.

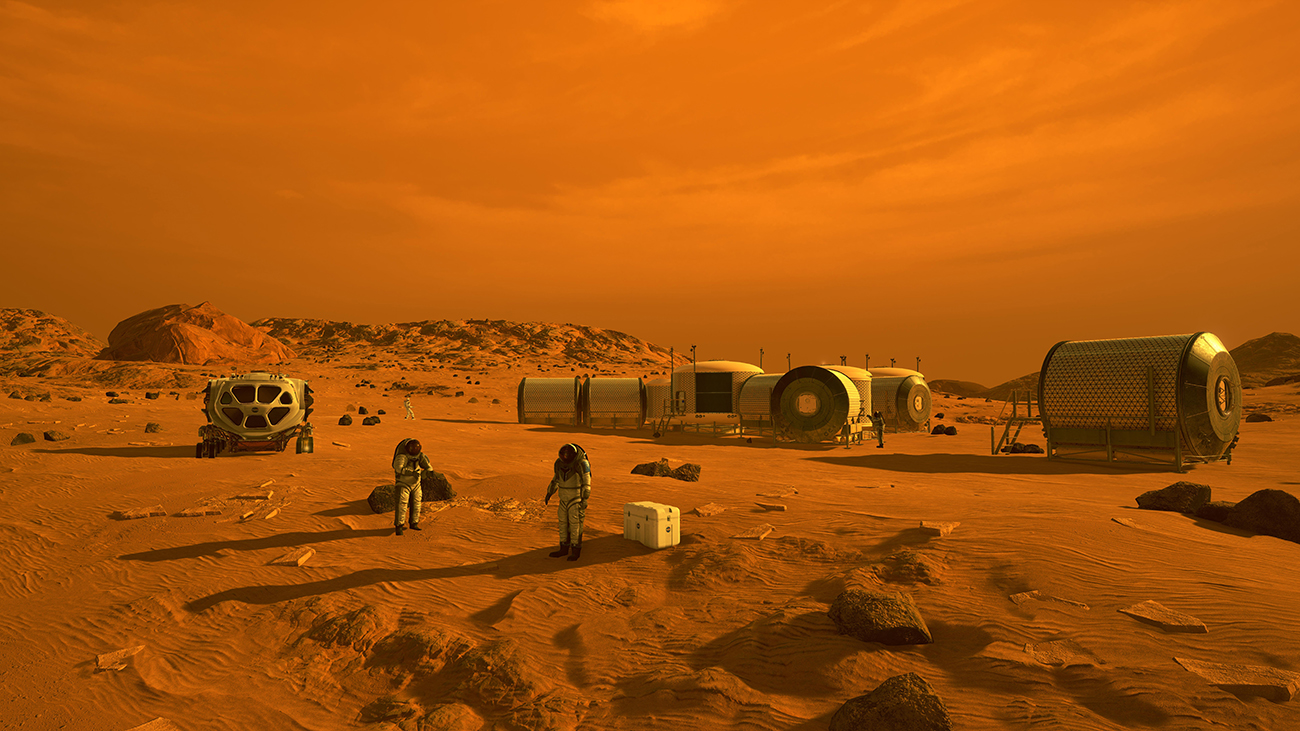

Space law says that countries cannot appropriate anything in the cosmos — but it doesn’t say anything about private actors or businesses. People already have plans to have Martian colonies, lunar colonies, asteroid mining. Those sound like property claims, right? Do these activities violate OST? If they do, that’s a big problem. If we don’t close up these legal gaps, we’re allowing this Wild West environment to happen.

Gold rushes, land rushes — they never lead to anything good. Resources get exploited. Workers get exploited. Some people get rich. Most people don’t.

Most countries in the world are not spacefaring nations, but many countries benefit from outer space. Someday they could have the capability to go up. As a lead country up there, if we ruin it for everyone else first, that seems very unethical.

There’s another issue with space colonies. You might have heard Elon Musk wants to start a Martian colony. You could be a part of it, and you wouldn’t have to pay for the trip — you could just agree to work off your debt working for Elon Musk on Mars. Those types of agreements have always worked out well, right?

An artist’s concept of a future crewed mission to Mars, the first step toward a possible human colony on the Red Planet. Image courtesy of NASA

Space debris is another big issue. Of the 35,000 to 50,000 items we track in space, only about 20% of them are working satellites and the rest is junk. Broken pieces of satellites and spacecraft are traveling at incredible speeds — around 10 miles per second. That’s about 10 times the speed of a bullet. Not to mention there’s also millions of bits of space debris that are too small to accurately track. If any of those collide with a space station or a satellite, that’s a huge problem.

There’s a concept called the Kessler syndrome, a possible tipping point when there’s so much space debris that it starts colliding with each other in an uncontrollable, unpredictable cascade of chain reactions. It just keeps propagating until the Earth is completely enveloped in a cocoon of space debris, so we’re effectively imprisoned by a floating minefield. Some experts say this is already starting to happen, but it’s clear that it could get much worse. So it’s important to clean up space debris while we can, but here’s another problem with that: Outer space treaties don’t have an abandonment clause. If you launch a satellite, you own it forever, even if it breaks up.

There are plans to develop space debris companies, using robots or satellites to approach debris with a claw or a tractor beam or a laser. The problem is, if space debris is always owned by some state or company, then you can’t legally touch it without their permission. Some of those objects might have sensitive information. You might have a dead satellite with servers that the owners want back, and we definitely don’t want the Russians coming to capture our stuff and say, “We’re just cleaning up your junk, don’t worry about it.” If we don’t want them to do it to us, we probably shouldn’t do it to them.

Given that, as you’ve mentioned, no one is really governing any of this, what are some ways we can prevent harmful outcomes in how we approach space?

I think the first step is we’ve got to recognize that no one’s coming to our rescue. This is all on us, so we’ve got to all play nice.

Imagine all these countries are living in a glass house. If we were to start throwing rocks, that could really bring down the whole house. It’s the same with outer space. It’s a fragile system and if we make the wrong choices, that could wreck everyone’s ability to use it.

We’ve got to find a way to cooperate. We’ve got to find a way to turn self-interest into cooperation, or we’ve got to find some common ground. Ensuring that we can continue to use orbits, for instance, might be a good starting point.

Ideally, we would close up the legal gaps by revising or clarifying our space treaties. But that’s really hard to do, especially right now, when the U.S., Russia and China are not on the best terms. I don’t see a lot of cooperation, but there is some. If you think about the International Space Station, that might be the one example where Russians and Americans are playing nice. There’s no politics in the ISS, they’re just doing science. I think if we could increase those opportunities for cooperation, those are little baby steps that could add up to something bigger.

A SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket lifts off from Cape Canaveral Space Force Base on an uncrewed mission to deliver cargo to the International Space Station. Photo courtesy of NASA

Another step would be to create more trust- and confidence-building measures. We could invite countries with whom we already have space treaties, or even competitor states, to come visit our facilities and see our space assets and vice versa. That could reduce distrust, because right now we don’t really know what the Chinese and Russians are sending up there.

We’ve got to find a way to turn self-interest into cooperation, or we’ve got to find some common ground.

And then it’s a good idea to do more to share benefits with other states, non-spacefaring states, because they’re stakeholders too. Space doesn’t just belong to the Americans and Russians and Chinese — if it belongs to anyone, it belongs to everyone. If we’re benefiting from space, whether through space mining or scientific discoveries, those ought to be shareable with everyone. That promotes trust and everyone can start rowing the same direction if they know that they’re all going to benefit, rather than just seeing the superpowers fighting in outer space while everyone else is struggling to live on two bucks a day.

From a philosophical standpoint, what does it mean to develop a set of shared ethics for a given situation, especially something like this, where the challenges and the possibilities are still emerging?

In any frontier situation, whether it’s the Wild West, the high seas, the Arctic or space, it’s not clear how law and policy work. When law and policy are unclear, ethics can be the North Star. Ethics can be this moral compass that points the way for law and policy.

That’s the tricky part, because different cultures might have different values. Even liberty and freedom might not be universally valued. You might have to zoom out and look for common ground at a macro scale: peace and prosperity and being able to flourish as individuals. That can mean different things in different countries, but at least there’s some common ground to start from. That at least gives us a foothold on ethics, a North Star that we could follow as we evolve a shared set of values.