Fighting Fires with Social Media

Wildfires spread quickly, but so do tweets. Alumnus and Cal Fire Chief Jonathan Cox explains why he uses social media to communicate in a crisis.

It’s more than just a hunch that West Coast wildfires feel more intense these days. The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (or Cal Fire) reports that nine of the state’s 20 most destructive wildfires in recorded history have happened since 2015. Almost all of those recent blazes raged in Northern California.

“This trajectory we’re on in California is not sustainable,” says alumnus Jonathan Cox (Agricultural Business ’03). He has been on the front lines of many of those disasters as a firefighter, battalion chief and public information officer for Cal Fire in the Bay Area.

Cox got his start as a volunteer at Cal Fire’s San Luis Obispo station just off Highland Drive near campus. The former Poly Rep would fight fires in the summer and on weekends, giving him a valuable “reality check” on what the real world is like outside of classes.

After nearly two decades with Cal Fire, Cox now serves as division chief, leading operations for San Mateo County Fire, where he is a trusted source for media from the containment lines. He has seen firsthand how the onslaught of major wildfires has converged with another seminal shift — how information flows through the digital landscape.

“You can’t be callous with the information. It’s just as important as putting the fire out.” – Jonathan Cox

In years past, Cal Fire depended on traditional media to filter and distribute news from formal press conferences or statements to the community. Now Cox and many public information officers have embraced social media as a way to inform the public and the media simultaneously about rapidly changing conditions, evacuation orders and life-saving instructions.

A glance at Cox’s Twitter account shows how his approach works. The feed serves as a hub for fire updates from around California. He shares insights from his post as command staff member for one of the state’s six incident management teams, which take over once a major fire has overwhelmed local resources. He also acts as a spokesperson for Cal Fire when blazes ignite, providing context for media outlets locally and nationally.

With the power to inform thousands of residents with the click of a button, Cox doesn’t take the responsibility lightly. He aims to be the public’s advocate within Cal Fire while feeling the demands of accuracy and timeliness.

“You can’t be callous with the information,” says Cox. “It’s just as important as putting the fire out. The way you present it and when you present it is paramount. If we don’t keep the public up to date or informed or engaged, the trust can be lost very quickly.”

The right information — like a red flag warning or road closures — can be the difference between life and death, Cox says. Take this example: the 1964 Hanley Fire burned from Calistoga to Santa Rosa in just over four days, charring fewer than 100 cabins in the process. In 2017, the Tubbs Fire burned the same area in three and a half hours, eventually destroying 5,500 homes and killing 22 people.

“I have two young daughters. On the Tubbs fire, it was about a week in, and I remember a father standing with his two daughters in front of their house that had been destroyed,” recalls Cox. “I felt like I kept it together pretty well up until that point … and that [moment] kind of brought it all home.”

While tracking the acceleration of these fires, Cox says Cal Fire has measured increased nighttime temperature and decreased degrees of moisture present in fuel like brush and trees. “Those indicators have both been going in the wrong direction,” he notes. “For us it’s undeniable that the changing climate is having an effect on how fires are behaving.” Those conditions, paired with development sprawl in hard-to-defend geography, mean hundreds of communities stand face-to-face with possible disaster during a now year-round fire season.

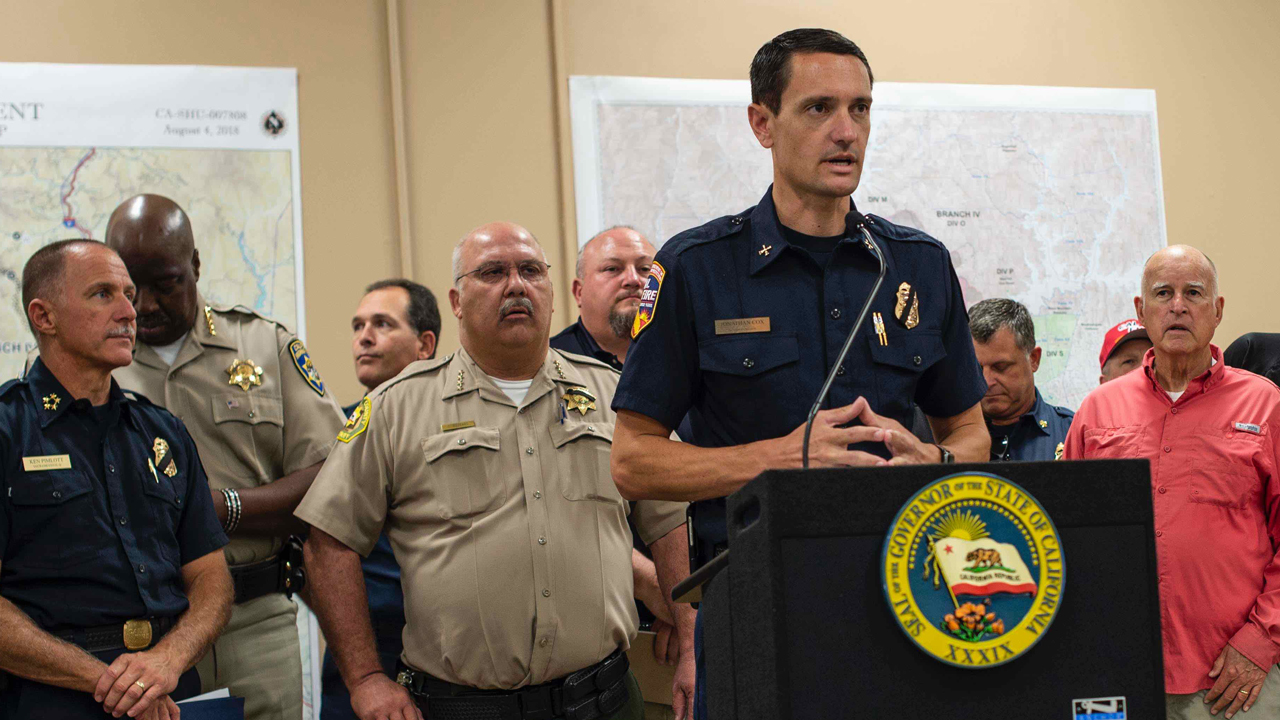

Fire Chief Jonathan Cox addresses leaders, including former Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen, in Redding, CA, during the Carr Fire. Image courtesy of Cal Fire.

As blaze after blaze exhausts Californians, Cox knows his job is also to be a calm, steady force in moments of chaos. That’s why he imagined himself as a firefighter even as a kid: to be an agent for good in his neighborhood.

“Early on in the North Bay fires, I had a reporter give me a huge hug and ask, ‘Are we going to survive?’ and I said ‘Of course we’re going to survive. Don’t worry.’”

Cox has some reason to hope. He’s excited by new technology — including sensors and cameras — that detect new blazes quickly. That information, along with more strategic evacuation management, will make a big difference in lives saved and damage prevented, Cox says.

In his own career, Cox still considers his alma mater the source of his success. “Cal Poly is the single biggest reason that so many good firefighters come out of San Luis Obispo County,” he says, referring to experience he gained while still a student. “It was a launching pad for my life and my career in both friends and my profession.”

If you live in the Bay Area, follow Cox on Twitter @firechiefcox for regular Cal Fire updates, or go to readyforwildfire.org for tips on preparing for a fire.

What can you do to help?

By now, most people know that defensible space (the physical distance between a structure and surrounding trees and brush) is the most important way to help people and homes survive a major fire. What else does Fire Chief Cox want you to know about keeping your community safe?

Know your neighbors.

“What we’ve seen on all these big fires, the Camp Fire specifically, is that those nearly 90 people who died were either elderly or vulnerable. It comes down to neighbors helping neighbors. If you live near someone, go and check on them in a crisis.”

Be careful outdoors.

“Take a red flag warning for what it is. That’s extremely important. When we have these red flag warnings with high winds, I can see people start to treat it like tornado warnings in the Midwest.”

Understand where you (or your local government) can build.

“[Encourage] smart development in California. That’s something people can do — be really considerate about where they live. What are the fire implications of putting new homes in certain areas? There’s a lot being highlighted right now at the city and county levels.”