The Family Who Helped Build SLO

President Armstrong celebrates the legacy of an iconic San Luis Obispo family with a strong Cal Poly connection.

President Jeffrey D. Armstrong

I was recently asked to say a few words about San Luis Obispo legend Ah Louis, and as I learned more about him, I got to thinking about how large an influence a single person can have on a community, and on the larger world around them.

As many of you no doubt know, Ah Louis, also known as On Wong, was a pillar of the San Luis Obispo community, and in particular of the Chinese and Chinese-American communities — he was frequently called the “mayor of Chinatown.” His store, at the corner of Chorro and Palm streets, began as a wooden building in 1874, and was replaced in 1885 by the handsome two-story brick building that still stands today.

Among his many business interests, Ah Louis acted as a labor contractor, bringing Chinese workers to many projects, including building a number of roads in the county, the Port San Luis Wharf, the Harford Pier (still in use), the stagecoach road on the Cuesta Grade (part of which is still open to traffic), draining the swamp around Laguna Lake, helping to build the Pacific Coast Railway that connected San Luis and Port San Luis (today’s Bob Jones Trail runs along the old PCR right of way), and helping to dig the tunnels through the Cuesta Grade needed to connect the Northern and Southern California railroads (five of them still in use) and create a statewide rail system. These last two projects were essential to connecting the county to the state, national, and global economies, and it is no overstatement to say that they changed the course of local economic development.

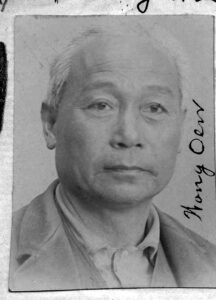

Ah Louis in 1894.

Ah Louis also acted as a bridge between the Chinese and white/Anglo communities, and the store was the center of large celebrations of the lunar new year until the 1930s, when the Chinese population had dwindled to very small numbers, due in part to racism and hostility toward people of Asian ancestry (though San Luis Obispo appears to have been, on the whole, more welcoming than many other parts of California or the United States generally).

What you may not know is that three of Ah Louis’s children attended Cal Poly in the 1920s, including his eldest son, Young Louis, who studied Electrical Engineering. Young Louis and his wife Stella supported the Electrical Engineering program and its students for decades, supported Poly Royal — the predecessor of the current Open House — for forty years, and in 1953 — three decades after Young Louis had been a student — they helped found the Poly Chi Club, now known as the Chinese Students’ Association.

Young Louis spent a lifetime improving the experience of Chinese and Chinese American students and residents in San Luis Obispo, in part because of his own experience at Cal Poly. As he explained in a 1988 interview in Cal Poly Today (the predecessor of Cal Poly Magazine) he felt that he could “never finish repaying Cal Poly the favor of enabling a young Chinese to get ahead at a time when public sentiment was largely anti-oriental.” Surely that is one of Cal Poly’s proudest moments, and just as surely it was made possible in part by the role that Young Louis’s father, Ah Louis, played in encouraging mutual understanding and toleration in San Luis Obispo.

Both Ah Louis and Young Louis (and his siblings) had an outsized impact on their community, on Cal Poly, and on the world. Cal Poly’s Kennedy Library is proud to be the repository of the Louis family papers, and some of the collection can be viewed online.

By the way, some of the information I’ve shared today comes from an excellent student paper written by Mariah Fiske in 2018 and available through the Cal Poly Library’s Digital Commons collection.